By: Ousman F. M’Bai

Financial Crime, Regulation & International Asset Recovery Lawyer/UK

Founder: ProffMaxx (Gambia) Ltd (Ground Water Drilling Exploration & Production)

The MSGBC

The MSGBC basin has been one of the world’s most prolific regions for oil and gas discoveries, until the recent unprecedented oil discovery in Guyana surpassed it. The basin is estimated to hold about two billion barrels of oil and 25 trillion cubic feet of gas. Located onshore and offshore on the Atlantic coast of West Africa, specifically between Mauritania and Guinea Conakry, MSGBC is an acronym for the countries that comprise the onshore part of this geological province with interconnected maritime boundaries: Mauritania, Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea Bissau, and Guinea Conakry.

The basin covers a total land mass of about 340,000 km² and an estimated offshore area of 100,000 km² with water depths between 2000 meters and 4000 meters. This offshore area spans over the AGC (Agence de Gestion et de Coopération entre le Sénégal et la Guinée-Bissau), a joint maritime zone between Senegal and Guinea Bissau.

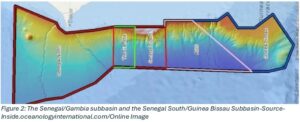

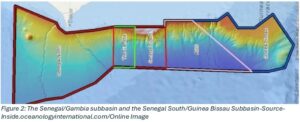

The basin is not a single continuous span but consists of three major connected subbasins:

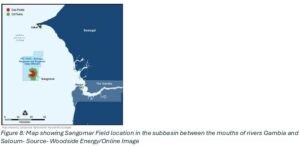

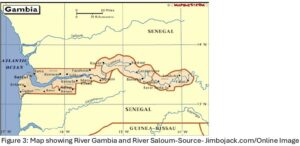

- Mauritania Offshore Basin: This basin stretches from the north of Mauritania down to the Senegal River in the southern border between Senegal and Mauritania.

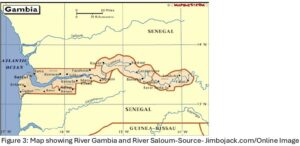

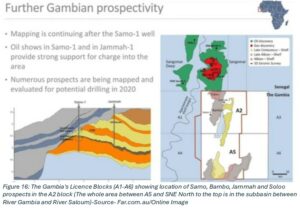

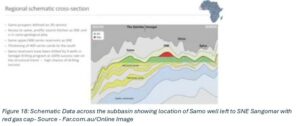

- Northern or Senegal/Gambia Subbasin: Located between the Senegal River and the River Gambia. The specific area of the subbasin relevant to this article is between the River Gambia and River Saloum.

- Southern Senegal/Guinea Bissau Subbasin: Extending south from the river Gambia through the Casamance region into Guinea Bissau.

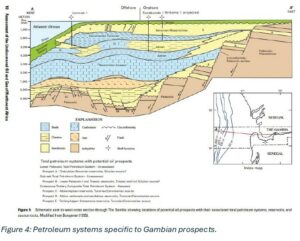

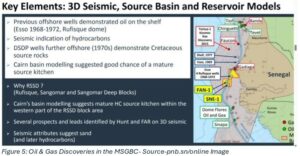

Geology of the MSGBC Basin

The basin developed in complex stages over millions of years, beginning with the opening of the North Atlantic and the splitting of North America from Eurasia and Africa during the late Permian to Early Triassic period. This process continued into the late Jurassic when the breakup of Africa from South America began, culminating in the opening of the Atlantic, which was completed in the Albian period. Marine deposits began forming in the early Jurassic in Morocco, advancing southward as the sea encroached on the land, reaching the southernmost edge of the basin in the late Jurassic. The rock formation after the split is identified as ranging from the middle Jurassic to the Holocene, consisting of a carbonate-rock unit with varying thicknesses between 2,300 meters and 3,200 meters in the three subbasins.

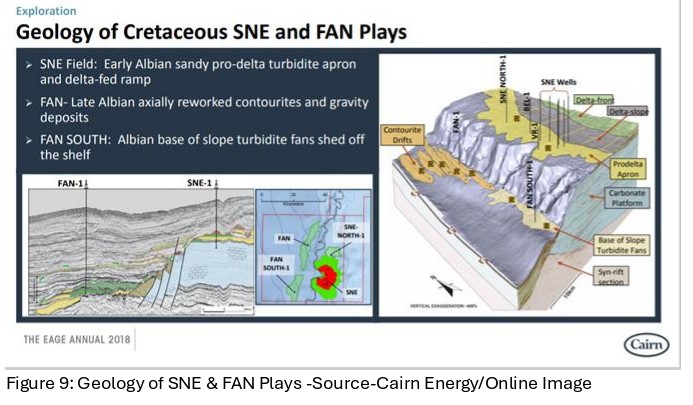

During the Albian, carbonate rock deposits continued to form progressively in the middle offshore part of the basin, known as the Northern or Senegal/Gambia basin, creating an elevated gradient. This feature is unique to this subbasin and is absent in the northern part of the Mauritania subbasin and the southern part of the Casamance subbasin, which are mostly characterized by deep-water sediments with shallow areas.

Cenomanian rocks, represented by thick marine shales sandwiched between marine sandstones, were deposited after the opening of the Atlantic. Widespread Turonian or Cretaceous rocks, commonly black shales often positive as hydrocarbon source rocks, range in thickness from 50 to 150 meters.

There is a mild westward sloping Mesozoic and Cenozoic platform, with a paleo shelf-edge trend between 35 to 100 km wide in the northwest, which balloons out to the west. It parallels the 2000-meter bathymetric contour before extending south across the Dome Flore offshore Guinea Bissau and Guinea Conakry. To the west of the paleo shelf-edge, in water depths greater than 2000 meters, sedimentary thickness exceeds 12,000 meters, and the formation is characterized by a curved fault plane that dips near the surface towards the edge of the Jurassic to lower Cretaceous platform.

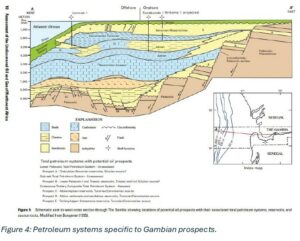

Hydrocarbon Source Rocks in the Basin

The total petroleum system of the basin is made up of three parts. The first part, lying on the Palaeozoic platform deep below sea level, is the lower Palaeozoic. Above this is the Mesozoic-Cenozoic platform, which supports the second part of the sub-salt system, consisting of Triassic and Jurassic source rocks. These rocks are potentially hydrocarbon-bearing, but they are so deep below the seabed that they are difficult to reach, and there has not been any exploration for oil or gas in this system. The third part is the Cretaceous-Tertiary system. These source rocks are confirmed to be hydrocarbon-bearing, and it is where most of the oil discoveries have been made. The Cretaceous-Tertiary system is subdivided into three zones: the lower Cretaceous, the upper Cretaceous, and the Tertiary. The lower Cretaceous is dominated by Aptian and Albian source rocks, the upper Cretaceous features Cenomanian and Turonian source rocks, and the Tertiary is characterized by Senonian-Maastrichtian sandstones.

Discoveries in the Mauritania/Senegal Subbasin

In 2015, Kosmos Energy using 3D seismic data made the largest global discovery of gas in the tortue-1 field which straddles the Mauritania and Senegal maritime boundary. Located at 120km offshore in water depth of 2,850m, the prospect has a projected recoverable gas resource of 15 trillion cubic feet. Further appraisal drilling in the area discovered the Guembeul-1 and Ahmeyim-2 wells in 2016 and the whole complex is now renamed The Greater Tortue Ahmeyim-1(GTA-1). In 2018, Senegal and Mauritania signed an inter-governmental co-operation agreement on an equal split of 50/50 of resource and revenue to develop to production this cross-border gas prospect. The project was given a unique status in 2021 as the GTA ‘National project of strategic importance’. The development is led by BP as operator, Petrosen (Societes des Petroles du Senegal (the Senegal State oil corporation)) SMH (Mauritienne des Hydrocarbon) and Kosmos Energy.

The unprecedented scale of this discovery intensified exploration further offshore in the deeper edges of the MSGBC basin with BP leading its joint venture partner Kosmos Energy. Their efforts paid off massively with the discovery of the Yakaar- Teranga gas field at water depth of 8,364 in northern Senegal. With an estimated 25 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas explorable to 2053, it was flagged as the world’s largest discovery in 2017. These discoveries are a lifeline to Senegal and Mauritania and if the revenue to be generated from them are managed efficiently, it will propel their economic growth for years to come.

Discoveries in the Southern Senegal/Guinea Bissau Subbasin

Guinea Bissau has recently experienced potentially transformative drilling explorations in its 11 offshore blocks within the subbasin. Newly acquired 3D seismic data has identified significant amounts of oil in the shallow reservoirs atop the salt-induced Flore Dome and Gea Dome. These structures are in a vast expanse of water in the Atlantic between latitudes 10.7◦N and 12.5◦N, known as the joint maritime zone between Senegal and Guinea Bissau.

The demarcation of these territorial waters followed a protracted disagreement between the two countries, with Senegal, aware of the natural resource potential of the area, insisting on a perpendicular delimitation of their maritime boundary. The dispute was amicably resolved with the establishment of the Agence de Gestion et de Coopération entre le Sénégal et la Guinée-Bissau (AGC). The AGC’s primary objective is to facilitate collaboration between the two countries in sharing resources to develop the oil and gas prospects in the area.

Recent developments in Guinea Bissau have revealed an underhand deal between the former President of Senegal, Mr. Sall, and his Bissau counterpart, Mr. Embalo, which has caused outrage among Bissau-Guineans concerning the prospective revenue split between the two countries at production. More details on this will follow.

Discoveries in Senegal – The Gambia subbasin – FAN-1, SNE & Sangomar Field

The discovery of the SNE-1 Sangomar field has ignited debate about its exact geographic boundary and whether it extends into The Gambia’s maritime area. These debates intensified in June 2024 when Senegal produced its first oil barrel from a well in the field, making it the newest oil-producing nation in Africa. This journey began in 1960, when the Senghor Government prioritised promoting investment in oil and gas exploration. Although Senegal’s first oil well in DiamNadio in 1960 was not commercially viable, it spurred successive governments to introduce policies attracting foreign investment. Significant reforms began under President Abdou Diouf and continued more vigorously under his successor, Abdoulie Wade. Wade succeeded in creating a stable and predictable environment for multinational investors, a policy continued by his successor, Macky Sall.

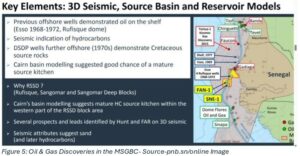

FAR Ltd, an Australian company focused on African oil and gas exploration, acquired licenses for three contiguous Senegalese blocks (Rufisque, Sangomar, and Sangomar Deep) in 2006. Incorporated in Western Australia in 1984 as First Australia Resources NL, it became FAR Ltd in 2010. These blocks cover 7,500 km² in the productive MSGBC basin, located in the Senegal/Gambia sub-basin.

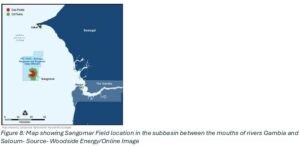

The blocks contain four prospects. On the paleo shelf-edge trend running between the mouths of the Saloum and Gambia rivers, about 50 km offshore, are SNE-North-1 and SNE-1 (Sangomar Offshore). The SNE-1, renamed Sangomar Field Development Phase 1 (SNE-1 Sangomar) by President Macky Sall, is contiguous with the northern edge of The Gambia’s A2 block. The deeper water prospects are Sangomar Deep FAN-1 and FAN South-1.

In 2013, FAR Ltd made a strategic decision to buy the licenses, previously held by Hunt Ltd, including modern 3D seismic data covering targeted 2,050 km² of the blocks. FAR Ltd enhanced the data, identifying hydrocarbon layers in the FAN-1 and SNE-1 fields and mapping four initial drillable prospects, followed by another seven. However, as a small venture capital company, FAR Ltd lacked the capital and expertise to drill offshore wells, prompting it to seek joint venture partners. FAR Ltd farmed out 85% of its license interest to Cairn Energy (operator, 40%), ConocoPhillips (35%), and Petrosen (10%).

At the time, FAR Ltd.’s Managing Director Cath Norman said:

“We are very pleased to have secured leading independent Cairn Energy as a farm in partner and Operator in our Senegal Project. With this agreement FAR has secured a highly experienced Operator to drill and fund it through the first exploration well to be drilled off the Senegalese coast for some years.

Cairn Energy funded most of the exploration costs and paid FAR Ltd.’s past costs, running into millions of dollars. The first well, FAN-1, was successful, revealing a gross oil-bearing interval of 500 meters with potential recoverable oil resources of 2.5 billion barrels. Cath Norman, FAR Ltd.’s Managing Director, highlighted the drilling risks and uncertainties about source rock capacity:

‘One of the key risks out here is that the presence of source was unknown. We know in this part of West Africa the source rocks turn on and off. And whether they exist out here to have the capacity to be filling the billion-barrel traps that we had mapped was a complete unknown to us. So, seeing a 500-meter oil interval is a great start’.

The SNE-1 Sangomar field, with a footprint of 400 km², was forecast to have a recoverable oil resource of 641 million barrels, the biggest discovery in Senegal’s history. FAR Ltd was awarded the Breakthrough Company of 2016 by the Oil and Gas Council Africa. The field also contained significant gas reserves. Cath Norman, describing the drilling team’s encounter with the field in one of her representations said:

‘Field was in fact larger. It was not until we drilled the 4th well that we stepped out of the gas cap and managed to intercept some of the secondary reservoirs in the oil leg. We are now four times the size of the field when we originally mapped it.’

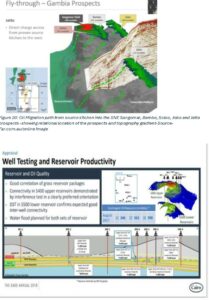

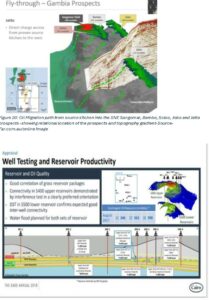

Ms. Norman described the field’s geology: a carbonate platform with extensive oil reservoirs in stack formation. The deeper S500 series reservoir is in the lower Cretaceous, while the upper S400 series reservoir is in the upper Cretaceous, topped by a gas cap. Connectivity tests confirmed good inter-well connectivity in both reservoirs. Indeed, Ms. Norman touched on this when she said in a presentation:

‘Connectivity is the last piece of the puzzle we need to resolve. Our field is really a field of two primary reservoir families. There is a deep reservoir unit which we call our 500 series. It’s made up of thick and blocky sand. They are lovely and young and clean with great porosity.’

She continued:

‘The upside is that the cream on the cake is proving a lot more of the connectivity of the thin sand that sits above the 500 series. We call that our 400 series and the focus of our next two wells will be which our JV are committed drilling in Nov to flow test some of those upper sands and also running interference tests which involves setting gauges, setting up the wells to be listening wells and then drilling a pulsing well and then looking at how those pulses proliferate across the thin sand. We will get a measure of connectivity of how continuous they are across the field’.

In fact, those connectivity tests were done, and Cairn Energy confirmed in one of its Appraisal Reports in 2018 that there was good correlation of the gross reservoir packages. It reported that connectivity in the S400 upper reservoirs was demonstrated by interference tests in a clearly preferred orientation and that the DST in the S500 lower reservoir confirmed expected good inter-well connectivity.

Ms. Norman has confirmed this because in the concluding part of her presentation she said:

‘Each well we drilled in the appraisal programme confirmed that we have 100meter gross oil column across all of the wells. We have the same high quality 32-degree oil quality across all the field, and we have good correlation between all of our principal reservoir units’.

FAR Ltd.’s success in Senegal was largely due to its joint venture partners, particularly Cairn Energy, ConocoPhillips, Petrosen, and later Woodside Energy. The type of drill rig used also played a significant role. Norman noted the difference in performance between the 5th generation semi-sub vessel and the 7th generation drill ship, which reduced non-productive rig time significantly. This is what she said:

‘When we drilled our first two exploration wells, we had a fifth-generation semi subcontracted for the drilling at $650,000 a day. That is just the rig rate not the total spread. When we drilled four appraisal wells some 18 months later, we contracted a rigg for $330,000 a day. It was a seventh-generation drill ship and performed immensely better than the semi-sub we had on our first drilling mission. We are just in the process of tendering for a rig now for our drilling programme in Nov. Looks likely we will be able to secure the equivalent of a seventh-generation drill ship for under $200,000 a day. Cost of drilling has come down by two-thirds. What is actually more important to us is the efficiency of the drilling. When we drill our first appraisal well, we had 70% non-productivity rig time. Which is abysmal. We had out 10% non-rig time for the four other appraisals well we drilled. And on one of the well, we had 3% non-productivity rig time. So, our JV is moving ahead very quickly now to secure rigs for continuing with appraisal and getting on with development drilling’.

FAR Ltd.’s entire operational focus was in the SNE-1 Sangomar field and the company given its long presence in Senegal from 2006 had developed deep connections and working relations at the highest level within the government, the office of the President of Senegal who at the time was Mr Macky Sall.

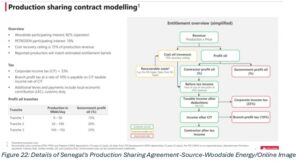

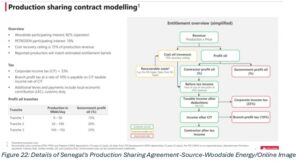

Today, there are more than twenty-three successfully drilled wells in the SNE-1 Sangomar field, and the first oil barrel was produced in June 2024. The revenue split is 82% for Woodside Energy and 18% for Petrosen. FAR Ltd.’s previous 15% stake in the field will be discussed later.

Oils and Gas Exploration in The Gambia

The Gambia’s foray into oil and gas exploration can best be described as sporadic. Between 1965, when it gained independence from Britain, and 1994, the country saw limited exploration activities. During the First Republic under Sir Dawda Jawara (1970- 1994) and the early years of the Second Republic under Yaya Jammeh, exploration efforts were scattered and intermittent. Some companies were involved in early exploration in the 1950s, but these were limited in scope and consisted mainly of initial studies. The country’s first oil well was drilled by Chevron in 1979, but it was not successful. This lethargy for oil exploration may have been shaped partly by Britain’s limited economic view of the country. During the colonial period, Britain saw The Gambia as an insignificant peanut-producing territory within its larger colonial empire. Britain showed little interest or enthusiasm for the economic development of the country beyond maintaining the lucrative supply line of raw peanuts to the UK.

Britain was circumspect about The Gambia’s viability as a state given its small size, being a narrow strip of land within Senegal with a tiny coastline on the Atlantic Ocean to the west. When the movement for independence began to gather unstoppable momentum, there were diplomatic discussions within the United Nations about whether merging with Senegal might be a better prospect for the country. However, this plan never advanced beyond discussions, and The Gambia was left to map its own path when Britain departed in 1965. The country had already been affected by British colonialism; before colonization, The Gambia was a much larger territory, with its northern border deep inside Sine Saloum near Kaolack, Senegal. British traders preferred to stay close to the banks of the River Gambia (no more than 30km wide at its broadest). As a result, Britain abandoned much of the territory to the French, who expanded further into The Gambia in 1850, reducing it to its current size.

For much of the 60s and 70s, while Senegal was busy exploring its oil and gas prospects both onshore and offshore, the government of Sir Dawda Jawara in The Gambia remained largely indifferent to the vast natural resources in and around the country. This lack of curiosity and ambition was evident when, in 1975, The Gambia agreed to its northern and southern maritime boundaries with Senegal along parallel equidistance lines running 200 meters east to west from the territorial sea baseline to the outer edge of the continental shelf. By that time, Senegal had a far better understanding of its offshore natural resources and readily agreed to the deal. The Gambia effectively shot itself in the foot, closing the door to an unimaginable National Wealth Fund from oil and gas that could have transformed the country’s socioeconomic development for generations if managed properly. A much wiser agreement would have been a perpendicular line on either side of the maritime boundary with common zones of mutual control with Senegal. All the SNE-1 Sangomar acreage would have been in this zone, rendering much of the discussion in this paper irrelevant. This approach is exactly what Senegal agreed upon with its southern neighbour, Guinea Bissau, maximizing its current oil and gas prospects in the AGC.

The Jammeh Era

Much of the credit for the limited progress The Gambia has made in oil and gas exploration goes to the government of Yahya Jammeh, who, for the first time in the nation’s history, established a Ministry of Petroleum in 2002. His government included policies for oil and gas exploration and development in its National Development Plan. The National Energy and Petroleum Act 2004 was passed into law, although it was largely based on legislation from Ghana.

Oil and gas exploration licences were made available for six separate blocks offshore The Gambia. Erin Energy was one of the first companies to acquire a licence for one of the blocks. However, there was a problematic period when several of the licenses were traded among insiders, with little benefit to the country. A case in point is the licenses in blocks A1 and A4 granted to African Petroleum Ltd, a company then majority-owned by Mr. Frank Timis. Mr. Timis, a Romanian-Australian billionaire, is a controversial figure in the oil and gas scene in West Africa. His activities in the subregion were negatively highlighted in a 2019 independent investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and BBC Africa Eye. Although oil was reportedly discovered offshore in 2003, Mr. Jammeh publicly criticised what he considered to be an insultingly low production sharing percentage offered by the exploration companies at the time. He declared that he would rather leave the oil in the ground than agree to an unfair sharing agreement. Jammeh’s intransigent conduct in this regard betrayed his intelligence. He failed to realise the importance of opening dialogue with Senegal for joint exploration and production in Sangomar, especially at a time when Senegal had made significant progress. Unwittingly, he too failed The Gambia.

Since then, there had been limited activity in oil and gas exploration until after 2016, when Jammeh was forced to leave office following his loss in the general election to Adama Barrow. Jammeh initially refused to hand over power but eventually went into exile.

Enter FAR Ltd – The Gambia

FAR Ltd entered The Gambia during a tumultuous period in the nation’s history, marked by elevated uncertainty and disarray as a new government struggled to assert control after two decades of brutal dictatorship. Government institutions were either not fully functional or non-existent, and there was no effective regulatory environment for oil and gas exploration. FAR Ltd quickly established a subsidiary, FAR (Gambia) Ltd, and acquired the 100% interest held by Erin Energy in The Gambia’s A2 and A5 blocks. These blocks are located south of the SNE-1 Sangomar field offshore Senegal, covering 2,682 km² within the MSGBC basin, specifically the Senegal/Gambia subbasin, about 50 kilometres offshore in water depths ranging from 50 to 1,200 meters. FAR Ltd forecasted a recoverable oil resource of one billion barrels in the blocks on an unrisked best estimate of 100%.

The license deal, giving FAR Ltd 100% working interest in blocks A2 and A5, effectively meant The Gambia owned none of its oil and gas resources upon discovery. All rights to explore, drill, produce, and sell resources from the blocks belonged to FAR Ltd and other licence holders. The Gambia had imprudently hinged its hopes on royalties’ payment at production. This arrangement, despite any savings The Gambia might have made from associated expenses, was to say the least, disadvantageous. Even Senegal had the foresight to retain an 18% interest in its blocks.

The exact terms of FAR Ltd.’s original licence have never been publicly disclosed. What is known is that FAR Ltd often referred to a minimum term of drilling one exploration well a year. Details about performance-related clauses, supervision, frequency of reviews, and dispute resolution mechanisms remain unknown. These elements are crucial in properly drafted commercial agreements but are often watered down or omitted in the African context.

FAR (Gambia) Ltd operated with a small team, including an Australian Asset Manager, reportedly based in The Gambia for some time. FAR Ltd would have had a good idea of working practices in The Gambia. The team was housed in the same building as the Ministry of Petroleum. Cath Norman from FAR Ltd highlighted that this proximity facilitated better and easier cooperation with the government.

Just before FAR (Gambia) Ltd.’s contractual drilling commitments in The Gambia were due, FAR Ltd claimed financial difficulties, as it had done in Senegal. Fortunately, Petronas, a major Southeast Asian oil and gas company, agreed to farm-in, initially taking a 40% interest in the A2 and A5 block licenses, later revised to a 50% split. FAR Ltd was the operator under the licenses, despite lacking prior experience in the MSGBC basin. Petronas had the option to assume the role of operator, though the terms and conditions were never made public.

To facilitate the deal, Petronas established a subsidiary in The Gambia, PC (Gambia) Ltd. Exploration and drilling activities were purportedly channelled through these two Gambian-registered subsidiaries in whose names the licence blocks were held. Board memberships and financial details of these companies have not been publicly disclosed. Notably, the lawyer retained by FAR Ltd for its subsidiary, FAR (Gambia) Ltd, shares chambers with their mother, a domestic PEP who has represented several parastatals and the country’s largest local authority. A former Attorney General, she also has family ties to high-ranking government positions, including a brother who served as Minister of the Interior and head of the Gambia Civil Service.

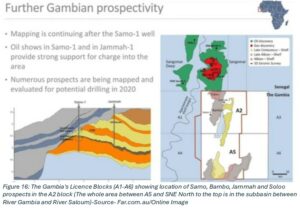

Samo-1 FAR Ltd.’s first well in The Gambia

The SAMO-1 well is located slightly off-centre within the A5 block on the PSET shelf edge trend. The reservoir sand for SAMO was deposited over 100 million years ago by ancient rivers that likely once occupied the area where the River Gambia currently flows. The SAMO-1 reservoirs were formed adjacent to where these rivers reached the coast. FAR Ltd forecasted a pre-drill estimate of 825 million barrels of recoverable oil on a 2P basis for this prospect.

In preparation for drilling, FAR Ltd claimed to have contracted a Stena DrillMax sixth-generation drillship and Exceed Ltd, a drilling management company based in Aberdeen, Scotland, to operate the drillship and drill the well. However, in a 2018 appraisal, Cairn Energy reported that no 3D seismic data was available for this prospect, suggesting that FAR Ltd relied on less accurate 2D data or none at all for its assessments. In an interview with Gavin Collery, Ms. Norman of FAR Ltd stated that 3D seismic data was available, but her remarks seemed to conflate the SAMO-1 well with the Bambo well, which is known to have undergone 3D mapping.

Lacking the necessary expertise and financial resources, FAR Ltd required Petronas to fund the project. Ms. Norman acknowledged this in a 2017 interview with Mr. Collery, stating, “It’s always best practice and prudent to bring a partner in when you have got a large equity position both to ratify your technical evaluation but also to share the cost.”

Later, in a presentation, Ms. Norman added, “FAR will continue to operate both licenses through the exploration phase, including the drilling of Samo-1, although Petronas will have the right to become the operator in the development phase.”

Despite these assertions, the actual drilling of the SAMO-1 well remains unclear. FAR Ltd was initially expected to handle the drilling, but this is complicated by a statement from FAR Ltd.’s Asset Manager, Mr. Rolf Stork, who remarked, “Petronas carried FAR drilled one well, SAMO-1. We drilled it as an operator. Big undertaking for a small company like FAR.”

Ms. Norman further clarified Petronas’ supervisory role in the joint venture, stating, “Petronas brought in as partners JV. 40% each. Petronas carried us through the drilling of the exploration well.” However, the specifics of Petronas’ involvement beyond funding remain ambiguous, with no public disclosure from Petronas or PC (Gambia) Ltd regarding their activities in The Gambia.

The SAMO-1 well, reportedly drilled to a depth of 3,200 meters into the seabed, did not yield oil. FAR Ltd claimed to have continued collecting extensive logging data to evaluate other prospects. Initially believed to be an extension of the SNE-1 Sangomar field, post-drill evaluations revealed that SAMO-1 was not connected. Mr. Peter Nicholls, FAR Ltd.’s chief geologist and exploration manager, explained, “We came in structurally a bit lower… two structures instead of one big field. There was oil in the system, but it was not able to be trapped.”

FAR Ltd suggested that the oil might have migrated to the Bambo well in the A2 block. Mr. Nicholls noted, “The interesting thing about this Bambo prospect is that if you follow the migration path, where the oil from SAMO-1 is likely to end up is overlying that feature, potentially 300 million barrels or more.”

FAR Ltd.’s objective after the failed SAMO-1 prospect was to trace the oil’s migration path to an accumulation zone. Success depended on the accuracy of structural maps, predictions of sand characteristics in accumulation zones, identified fault lines, formations, shale types, and effective drilling. With modern drilling techniques and geophysical mapping, the role of luck is reduced, yet the question remains: why and how did FAR Ltd fail The Gambia?

The second well – Bambo-1 (side track-1) & Soloo

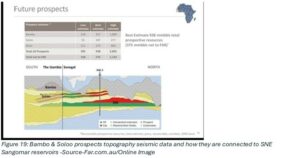

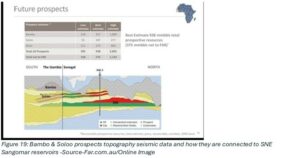

In 2020, FAR Ltd moved on to its next drilling prospects, the Soloo and Bambo wells. These are located to the north of the A2 block, nearly side by side on an elevated gradient of the PSET shelf trend, part of the SNE-1 Sangomar field extending into the A2 block. The available 3D seismic data predrill confirmed the geological formation as a continuous extension of the SNE-1 Sangomar field into The Gambia. FAR Ltd.’s Exploration Manager and chief geologist Mr. Nicholls noted:

“You could see that Soloo could well be an extension of the SNE. As a matter of fact, it’s very much mapped as an extension of SNE into The Gambia, and that is Woodside and other JV Partners in SNE will see that SNE does extend into The Gambia. So that’s not a contentious issue. It’s the way it’s seen and mapped as extending into our block.”

In a predrill presentation, Ms. Norman commented on the Bambo well:

“You can see clearly that the Sangomar oil fields extend south into The Gambia. In fact, the location of the Bambo-1 well is 500 meters from the border to the south, drilling into the extension of the Sangomar field that we call the Soloo prospect.”

The predrill forecast estimated recoverable oil from the Bambo-1 well at a billion barrels. FAR Ltd planned to drill through three prospects: Soloo upper, Bambo upper, and Soloo deep, categorized as the S390, S400, and S500 series, respectively. The Soloo upper in the S390 series had the highest chance of success at 36%. The predrill seismic data indicated that all three prospects were within the same depth and level as the primary reservoirs in the SNE-1 Sangomar field.

FAR Ltd again acted as the operator, reassembled the same drill team from the failed SAMO-1 prospect, and contracted the same Stena IceMax Drill ship (not the seventh generation vessel used by Cairn Energy in the SNE-1 Sangomar field). FAR Ltd reported that the drill rig was operational offshore Mexico, and this was advantageous as it meant FAR Ltd would not be using a cold stack rig. However, there was no disclosed verifiable evidence that this rig was service worthy and fit for purpose. FAR Ltd.’s headquarters was reportedly in Banjul, The Gambia, but the operational base was in fact in Dakar, Senegal, where supply boats delivered all necessary pipes and goods for the drill vessel.

In November 2021, FAR Ltd finalised well locations and commenced drilling soon after. In December 2021, FAR Ltd reported that the wells, particularly Soloo Deep, did not contain commercially viable quantities of oil or gas.

A subsequent press release stated:

“Bambo-1 was initially drilled to a depth of 3216m MDBRT (Meters drilled below the rotary table), and wireline logging was completed. The Bambo-1 well was then plugged, and the Bambo-1 ST1 (side-track) well drilled to a depth of 3317m MDBRT, after which wireline logging was undertaken.

The drilling and logging data from the main well and the side-track well indicated that several target intervals had oil shows, confirming a prolific oil source in the area. Initial interpretation of cuttings and wireline logging suggested these zones had oil in poor-quality reservoirs and in traps that might have been breached, leaving residual oil. Rocks and fluid samples were recovered from several intervals in the Bambo well, and laboratory analysis in 2022 will provide additional data about the oil potential identified in the Bambo well.

The Soloo prospect objectives in the Bambo-1 well, which represented the potential southern extension of the Sangomar field in A2, indicated some oil shows but no significant oil volumes. However, oil shows in the Bambo prospect reservoir, encountered in both the Bambo-1 and Bambo-1 ST1 wells, highlighted up-dip potential to the south in the A2 Block, mapped as the new Panthera prospect. Other reservoirs in the Bambo drilling campaign show oil potential, opening additional exploration opportunities in both the A2 and A5 Blocks.

The well and side-track have been plugged and abandoned as planned for this type of exploration drilling.”

The press release emphasised that the Soloo and Bambo-1 prospects were not

extensions of the SNE-1 Sangomar field. It did not clearly disclose that drilling had not

gone as planned. The drill rig had an accident at 3216 meters below the seabed, forcing

FAR Ltd to halt operation before reaching the target depth of 3450 meters MDBRT. They

then planned a side-track well, Bambo-1 ST1, which also fell short of the target zone.

FAR Ltd and its JV partner Petronas designated the well a ‘tight hole’ and released

minimal information during drilling.

The cause of the accident was unclear, and FAR Ltd did not provide details. Ms. Norman, FAR Ltd.’s Managing Director, commented:

“FAR is pleased with the experienced drilling team and contractors who quickly adjusted the Bambo-1 drilling program to suit the geological setting and best meet the drilling program’s objectives. FAR is well-placed to achieve these objectives through the side-tracked well and drilling through the undrilled Soloo Deep prospect. We are encouraged by the presence of oil in potential reservoirs and look forward to completing the well in the coming weeks.”

FAR Ltd.’s drilling programme appeared unfocused, attempting to drill through three separate reservoirs in a stacked formation—a technique not tried in the successful SNE-1 Sangomar field. This ambitious approach led to challenges, including a sudden loss of fluid mid-drilling, necessitating diversion through an unplanned side-track well.

Curiously, FAR Ltd made no reference to Petronas having any role in this drilling, unlike the SAMO-1 well. Instead, the company pointed to an unidentified drilling team and contractors. Several plausible reasons for this drilling failure include the inexperience of the crew, inaccuracies in the geophysical survey data, errors in seismic data interpretation, or an ill-equipped drill rig. However, given the geophysical team’s successful track record in the SNE-1 Sangomar field, it is unlikely they were the issue. The limited information available about the drilling crew suggests that FAR Ltd.’s inexperience as an operator was the main problem. The company failed to effectively coordinate the drill crew, drill rig, and geophysical team to overcome the complex drilling challenges.

FAR Ltd.’s finding of no commercially viable oil and gas in the Bambo-1 and Soloo wells contradicts the predrill 3D seismic data showing these wells as connected to the successful SNE-1 Sangomar field reservoirs. Ms. Norman stated predrill:

“The outcome of that process is that we have a net billion barrels of oil potential in our two blocks offshore Gambia. Following the risk audit of FAR’s evaluation of the potentials, we have confirmed a P50 un-risked 1.1 billion barrels of potential in The Gambia. We have always expected our acreage to be highly prospective because it is contiguous with our acreage in Senegal. We have drilled 11 wells offshore Senegal, 8 on the same trend that extends into The Gambia, and 8 into the same reservoirs that will be our primary reservoirs in The Gambia.”

(Emphasis underlined by author)

The 3D seismic data indicated that all the successful wells in Senegal’s SNE-1 Sangomar field were in the same primary reservoirs (S400 and S500 series) as the wells in The Gambia. The Gambian prospects were charged with oil, as proven by Cairn Energy and admitted by FAR Ltd, confirming that all wells in the S400 and S500 reservoir series are connected.

This raises the question: what separates the Soloo and Bambo-1 prospects from the SNE-1 Sangomar field? Is there a risk that FAR Ltd.’s finding—that its SNE-1 Sangomar field does not extend into The Gambia’s A2 block—is based on its failed drilling programme?

The Bambo and Soloo prospects have multiple reservoir targets, with two main reservoirs in the S400 series being hydrocarbon-bearing in the SNE-1 Sangomar wells. FAR Ltd has not identified at least to the public in the Gambia which reservoirs in the Bambo and Soloo prospects do not contain commercially viable oil or which targets may have been missed due to drilling failure.

A troubling coincidence is that the prolific SNE-1 Sangomar S400 and S500 series reservoirs suddenly do not contain commercially viable oil at the boundary line where the field extends into The Gambia. FAR Ltd claimed that the reservoir for the Bambo-1 well was poor and unable to trap oil due to seal breaches, the same reason given for the failed SAMO-1 well.

The geophysical features of the PSET shelf edge in the SNE-1 Sangomar field and the A2 and A5 blocks are nearly identical, formed over the same period and close in time and space. The reservoirs in the A2 and A5 blocks are good, but the seals, made of black/grey shales, are reportedly underdeveloped according to Far Ltd. If true, this suggests that the oil in The Gambian prospects has migrated into an unidentified accumulation zone.

FAR Ltd does not dispute this, but it raises the question: does FAR Ltd have a duty to consider and determine the phenomenon of oil migration from The Gambia?

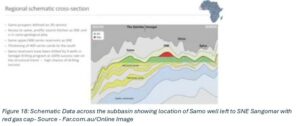

The Source Kitchen & the phenomenon of oil migration in the MSGBC – Senegal/Gambia subbasin

The hydrocarbon source ‘kitchen’ that feeds all the reservoirs in the SNE-1 Sangomar field lies deep below the seafloor of the basin, migrating up the slopes of the PSET trend in a westerly direction into the reservoirs.

The Soloo and Bambo prospects have easy access to this source kitchen, similar to other reservoirs in the SNE-1 Sangomar field. FAR Ltd.’s Ms Norman underscored this point in one of its presentations:

“I would like to walk you through what the exploration opportunity looks like for FAR. Starting with the Sangomar oil field, which is a known oil field sitting on the shelf edge of a carbonate platform being fed by oil generated in the source kitchen deep out to the west. You can see on the bottom left of the seismic line that I’m showing you is right through the Sangomar oil field, and I’m going to step through to the south to show you the prospects further to the south in the Gambia. The first, of course, are Soloo and Bambo that we’ll be drilling with the Bambo 1 well just to the north of our blocks in A2. You can see that they have easy access to the source kitchen and that source kitchen is very prolific to generate enough oil to house 5 billion barrels of oil just in place just to the north in Sangomar, which means we have a really rich source rock that’s capable of generating a lot of oil in this region. As we step further to the south, we have the Jobo prospect at about 280 million barrels, the Jato prospect at about 130 million barrels, and then Malo, a very large prospect out to the east at about 265 million barrels. All on a P50 best estimate basis. So, lots of follow-ups in our A2 and A5 blocks. We are not just about drilling Bambo this year.” [Emphasis underlined by author]

The migration path of oil into an accumulation zone or reservoir is directed by hydrostatic pressure exerted by gravity on the source kitchen. Often, the migration path follows natural fault lines within hydrocarbon formations. When these fault lines remain active and overlap with a trap, the trap becomes the main accumulation zone. The oil remains trapped in the accumulation zone if the reservoir is made of good porous sandstone or limestone and has mature seals to prevent further migration or degradation by water.

Apart from gravitational pressure, other key factors determining the migration path of oil into an accumulation zone or reservoir include buoyancy, the geothermal gradient of the hydrocarbon formation, the size of the fault lines, and the porosity and permeability of the reservoir sandstone. Primary migration and accumulation of oil may have started millions of years ago but can continue as long as the source kitchen releases oil and the fault lines are active, allowing secondary migration into other reservoirs.

The viscosity of the oil in the SNE-1 Sangomar field, at 32◦, makes it a light fluid, similar to the residual oil in The Gambian prospects. Therefore, it would migrate at a much faster velocity over long distances under normal geothermal conditions. Since The Gambia’s A2 block is physically contiguous with the SNE-1 Sangomar field, as shown by 3D seismic data, the migration of a large volume of oil from there into the SNE-1 Sangomar field would be quick and effortless.

The SNE-1 Sangomar field is at the centre of a geographic phenomenon in the Senegal/Gambia sub-basin, part of the MSGBC basin. It contains giant reservoirs or accumulation zones into which oil is fed from the source kitchen. It also serves as the most likely trap zone for oil migrating along the PSET shelf from different directions, particularly from The Gambia.

The acreage of the SNE-1 Sangomar field is unusually extensive. It sits on a depression on the PSET and has a lower gradient compared to the Soloo, Bambo, and SAMO-1 prospects in The Gambia. It supports two known separate gigantic oil reservoirs in stacked formation, the lower and upper reservoirs, with a substantial gas cap. These reservoirs are in lateral formation, separated by thick layers of ancient rock. The secondary migration paths into these reservoirs are confirmed to be through separate stratigraphic fault lines from the source kitchen in a west-to-east direction.

Basin modelling from FAR Ltd.’s exploration in the A2 and A5 blocks identified a secondary migration path running the length of the PSET from south to north, from SAMO-1 towards Bambo-1. The SNE-1 Sangomar field lies north on this migration path. If the oil in the SAMO-1 well could not be trapped due to a lack of mature seals (though it has a good reservoir) and its migration path is charted towards the Bambo and Soloo prospects as FAR Ltd has acknowledged, then those two are not the accumulation zones, as they are reported not to have oil in commercially viable quantities.

The oil must have migrated further into an alternative trap, and the most probable location of that trap, in terms of time, distance, and space, is the extensive SNE-1 Sangomar reservoirs.

The substantial gas cap on the SNE-1 Sangomar field is further evidence of the secondary migration of an enormous volume of oil into these reservoirs, particularly the S400 series. The gas cap resulted from thermal regeneration, where increased temperatures in the hydrocarbon formation caused chemical reactions that converted oil into gas. What remains in the reservoir is the current volume of oil that has not been heated into gas.

Oil reservoirs maintain equilibrium through hydrostatic pressure. When this pressure is disrupted at any point, the fluid will naturally flow toward areas of lower pressure. The giant S400 and S500 series reservoirs in the SNE-1 Sangomar field have had 23 wells drilled in them, and there could be even more. Numerous pressure tests conducted by FAR Ltd, and its JV partners confirmed the connectivity of the wells in those reservoirs. Therefore, the historic pressure within the reservoirs was disturbed well before it was determined whether the SNE-1 Sangomar field extended into The Gambia.

For obvious reasons, FAR Ltd. seems to focus its efforts on identifying a separate accumulation zone (however unlikely) for the prospects in The Gambia. Despite these efforts, the company has made little progress in pinpointing a distinct migration path and accumulation zone for the billion barrels of oil it once predicted in its Gambian blocks. It has been seven years since the drilling of the SAMO-1 well and three years since the drilling of Soloo and Bambo-1, along with the Bambo-1 sidetrack-1. Yet, FAR Ltd. has not provided any substantial updates on the extensive research it claims to be conducting on the logging data from these unsuccessful wells. Instead, the company is now shifting its focus to the Panthera, Jato, and Malo prospects within the A2 block, which are located in the same area and gradient as the Bambo well, in close proximity to the SNE-1 Sangomar field.

The question must be asked: Is it necessary for there to be a separate oil accumulation zone in The Gambia if geophysical analysis confirms that oil migrates or migrated from the Gambian prospects into the SNE-1 Sangomar field or across the maritime boundary into Senegal? If this is the case, what potential difficulties would FAR Ltd have encountered in navigating the contractual and political challenges that might have arisen, given that, before selling its stake in 2020, it partly owned the SNE-1 Sangomar field?

Specifically, this points to several issues:

- FAR Ltd.’s contractual relations with its joint venture partners in the SNE-1 Sangomar field.

- Its contractual relations with the Gambian government regarding the A2 and A5 blocks. This points to FAR Ltd.’s obligation under specific clauses dealing with development and production of the oil and the payment of royalties to The Gambia.

- The potential contentious issue of shared stakes between The Gambia and Senegal.

How might these factors have impacted the oil production revenue-sharing agreement and the production schedule of the joint venture partners in the SNE-1 Sangomar field if The Gambia were to assert its right to a share of the oil and gas? Woodside Energy and Senegal would clearly want to avoid any delays in their production schedule from the SNE-1 Sangomar field. It seems FAR Ltd was caught between a rock and a hard place!

The Law – Conflict – Natural Resources along/near to Maritime boundaries

Both The Gambia and Senegal are signatories to the United Nations International Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The convention does not specify how states should share or exploit natural resources between their maritime boundaries, nor does it address the migration of natural resources, such as oil, from one country into an accumulation zone across maritime boundaries. It encourages nation-states to adopt principles of equitable dealing, good faith negotiations, and respect for sovereignty in bilateral and multilateral agreements. These concepts often carry legal nuances that are challenging for courts and judges to apply consistently.

Natural resources below the seabed between countries are of strategic importance and require active cooperation between states to harness their value. However, the absence of international law detailing how ownership rights over these resources should be determined has led to “safari justice” in some parts of the world, where might prevails and weaker countries struggle to protect their interests. Another aspect of this issue is related to the jurisdiction of maritime boundaries. It is commonly assumed that strict adherence to surface maritime boundaries automatically determines ownership rights of resources deep below the seabed, which can lead to significant injustice. Oil and gas, for instance, are migratory substances that can cross maritime boundaries due to gravitational pressure differences. The Senegal/Gambia sub-basin of the MSGBC is exclusively shared by the two countries, and equitable principles suggest that its sub-seabed resources particularly in the area between The Gambia and Saloum rivers should be jointly shared. This should not be contingent on proving oil migration from Gambian wells to the SNE-1 Sangomar field. The aggressive stance of the Macky Sall government and the oil companies in the SNE Sangomar exemplifies the excesses of unchecked capitalism. At a deeper level, it also questions Sall’s moral value as a Senegambian.

The same principles of equitable dealing and good faith negotiations apply in private international investment agreements. Investors must perform their license obligations in good faith, which has both substantive and procedural perspectives. Substantively, it involves the host state’s obligations to the investor and vice versa. Procedurally, it refers to arbitration proceedings for dispute resolution. Good faith encompasses fairness, honesty, loyalty, and transparency, essential for maintaining justice in international investment law. It requires parties to comply with their obligations competently and with mutual trust and cooperation.

When there is a perceived conflict of interest or lack of transparency or competence in the performance of a license obligation by an investor, the state’s interests are vulnerable. Aside from FAR Ltd.’s failure to find a separate oil and gas accumulation zone in its Gambian blocks, was it within its competence to determine for the Gambian government whether the missing oil from the failed wells may have migrated into the SNE-1 Sangomar field? FAR Ltd had already charted the likely migration path of oil from SAMO-1 well to Bambo-1 well. Why stop there? If the hypothesis is valid that oil migrated from the Gambian prospects into the SNE-1 Sangomar reservoirs, how does that reflect on FAR Ltd.’s performance if the Gambian government lacks clarity on this issue? It is the responsibility of the Attorney-General (with assistance from external counsel if necessary) to advise the government on whether the investor has performed its obligations competently and in good faith.

This task is easier with the active participation of the government through a relevant regulatory authority, as demonstrated by Petrosen in Senegal during the development of their prospects. In contrast, the government of The Gambia was unable to take similar action. It had both hands tied behind its back, having given away 100% of its interest in both blocks. Unfortunately, the government could not rely on its Attorney General, Ministry of Petroleum, GNPC, or Petroleum Commission to intervene, for reasons apparent to most Gambians. Independent legal and geotechnical advice was urgently needed. Furthermore, the involvement of FAR (Gambia) Ltd.’s lawyer creates a potential significant conflict of interest, even in the absence of any clear indication of wrongdoing.

The Political Agenda – Senegambia

The legal framework for oil and gas exploration in The Gambia is complex, and the political landscape further complicates matters. FAR Ltd.’s performance in The Gambia’s A2 and A5 blocks has not improved the situation. FAR Ltd has effectively put a nail in The Gambia’s oil and gas exploration prospects by finding that the SNE-1 Sangomar field does not extend into The Gambia without fully addressing the potential migration of oil from The Gambia into the SNE-1 Sangomar field. This outcome benefits Senegal, where former President Macky Sall negotiated an extremely poor production sharing agreement, allowing Woodside Energy to retain 82% of the revenue while Petrosen, Senegal’s state oil corporation, received only 18%. Mr. Sall would likely have preferred to avoid any reduction in Senegal’s share, and FAR Ltd.’s findings reinforced this by negating The Gambia’s claim to exploration and production rights, unlike in Mauritania to the north and Guinea-Bissau to the south.

Senegal, under Macky Sall, adopted a silent but sophisticated policy of economically merging The Gambia with Senegal (a feat that could not be achieved politically during the Senegambia Confederation) by supporting a new regime in The Gambia that aligned with Senegal’s strategic interests. In 2016, this opportunity arose when former Gambian dictator Yahya Jammeh reneged on his promise to hand over power after losing the general election. Adama Barrow, the declared winner, fled to Senegal, and Macky Sall spearheaded diplomatic efforts in West Africa and the EU to force Jammeh out. He succeeded, and Jammeh fled into exile to Equatorial Guinea. Barrow was sworn in as President of The Gambia in Dakar, Senegal, and was escorted into the country by Senegalese security personnel. Since 2016, Barrow’s close protection officers and guards at the State House have been Senegalese soldiers and security agents. Barrow regards Sall as an elder brother, advisor, guardian, and protector against coups. The relationship between the two is more accurately described as subservient—anything Macky wanted for Senegal from The Gambia, Macky got. Their relationship, shaped by their differing levels of sophistication and experience in state affairs, appears to reflect an exercise of undue influence. One is a geologist with extensive senior government experience, while the other, despite being a successful estate agent and skilled money manager, is a high school dropout with no prior government experience. Many of Barrow’s government’s decisions since 2016 have effectively surrendered The Gambia’s economic sovereignty and security to Senegal—a gift that eluded Senegal since the two nations were divided by colonial history.

It is unsurprising that Barrow and his government have not made a single pronouncement regarding the country’s oil and gas prospects within its maritime boundary with Senegal. Even if he wanted to, achieving success would be difficult. Sall was notoriously corrupt and engaged in underhand deals. In 2021, Guinea Bissau’s president, Umaro Sissoko Embalo, signed a secret oil and gas sharing agreement with Sall, without informing his cabinet or parliament. The deal, unfavourable to Guinea Bissau, allocated only about 30% of revenue to the country. Armando Lona, editor-in-chief of O Democrata, criticized the agreement as illegal since it lacked parliamentary approval and accused the president of secrecy regarding national resources. The Guinea Bissau parliament revoked the agreement, and Sall sacked his energy minister, Amadou Hott, who did not dispute the agreement when challenged in a media interview.

Given Sall’s history, it is plausible that he has managed to silence Barrow and his government regarding oil and gas matters near their maritime borders. The opposition, parliament, and civil society in The Gambia have been silent on the subject, reflecting a lack of curiosity and ambition to safeguard national interests, reminiscent of the Jawara government during the First Republic.

There is a sense in The Gambia that discussing joint exploration, production, and revenue sharing of natural resources with Senegal is taboo, especially now that Senegal has started oil production. The commonly cited phrase, “The Gambia and Senegal are two heads of the same body,” discourages open discussion on the topic. Consequently, the government of The Gambia has failed, unlike Mauritania and Guinea Bissau, to foster intergovernmental dialogue about shared natural resources across maritime boundaries with Senegal.

As a result, Senegal is the sole beneficiary of a vast oil and gas field in the shared Senegal/Gambia sub-basin. Under normal circumstances, applying principles of equity, these resources should be shared, regardless of the discovered accumulation zone being on the Senegalese side. The Gambia’s failure to protect its share of the resources can be attributed to its weak institutions at every level. Since 2021, Mr. Jerreh Barrow has served as the sole Commissioner of The Gambia Petroleum Commission. The Commission is the authority responsible for overseeing resource exploitation, including monitoring and ensuring compliance with national policies and regulations for petroleum activities. A concerning clause in the model Production Sharing Agreement (PEPLA) stipulates a Signature Bonus to be determined by the Licensee at the time of bidding, in addition to a further $2 million payment required upon the Commissioner’s approval of the first Development and Production Plan. This payment structure also applies to any subsequent amendments or new development plans. Additionally, production bonuses of $10 million are to be paid at various stages of development. The clause links the payment of substantial bonuses to the Commissioner’s approval, which could raise concerns about potential conflicts of interest or corruption. A more robust anti-corruption measure might involve requiring approval from a board or committee rather than an individual, thereby enhancing transparency and accountability.

The Gambia National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC), responsible for encouraging petroleum operations, has abandoned initiatives to cooperate with oil and gas exploration companies as JV partners, unlike Petrosen in Senegal. The GNPC has been mired in corruption, limiting its activities to storage and distribution of petroleum products. A recent government task force, led by the Minister of Finance, found that despite having expensive computers and software, GNPC staff preferred manual entries, making record-keeping and transaction tracing difficult. Reports indicate that over $20 million has been misappropriated at the GNPC, which is just the tip of the iceberg.

BP (British Petroleum) exits The Gambia’s – A1 Block

It is therefore not surprising that BP exited The Gambia in August 2021 by surrendering its license in the A1 block. This block, along with the A4, had a chequered history. In 2006, African Petroleum acquired a 100% working interest in these blocks from Buried Hill Ltd. The licences were extended thrice, as it appeared the company was unable to fulfil its drilling obligations. When negotiations to extend the license failed, the government of The Gambia terminated the licenses for the blocks in 2017.

African Petroleum denied the termination, asserting that the government had not enacted the proper termination procedure and that its licenses remained in force until this was done. This led to an expensive and protracted arbitration proceeding lodged by African Petroleum at the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) against The Gambia.

The Government of The Gambia secured the services of Cherie Blair KC, wife of former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair. They secured the services of Cherie Blair KC, wife of former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair. At the time, Mrs. Blair, though well-respected for her advocacy in human rights and administrative law, did not have experience in international oil and gas arbitration proceedings. The case was led admirably by a legendary Gambian US-based attorney who provided distinguished service but without a decisive victory through no fault of his but the weakness of the Gambia’s case.

While proceedings were ongoing, the government of The Gambia, in an unprecedented act of disregard for the arbitration process, opened bidding on the A1 block and sold it to BP in April 2019 before the matter was concluded. The case was eventually settled with The Gambia surrendering the A4 block back to African Petroleum in September 2020. There has never been a public disclosure of the full details of the settlement and the legal costs incurred by The Gambia in the case.

It was partly through this case that certain individuals in The Gambia who prioritise personal gain over national development opened a secret passage (disguised under the name of the Tony Blair Institute) between Tony Blair, former UK Prime Minister, and the office of the President of The Gambia. On April 18, 2018, Mr. Blair hosted President Barrow at a discussion panel held at the famous Chatham House, Royal Institute of International Affairs. Mr. Blair is known within closed circles in The Gambia to have quietly jetted in and out of the country during the period leading to BP’s exit from The Gambia. What most Gambians do not know is that behind many seemingly charitable foundations operating in The Gambia are consulting businesses for profit. Cherie Blair KC heads Omnia Strategy, an advisory firm that has picked up a phenomenal workload in the short time it has been operating, largely from developing countries.

BP’s exit from the A1 block rendered the minor result in the arbitration case a Pyrrhic victory. At the time, the Gambia Ministry of Petroleum issued a press release indicating that BP had informed the government its decision to exit was due to a change in its corporate strategy towards low carbon energy. While this might be true, BP itself did not comment on the issue. The circumstances surrounding BP’s exit from The Gambia raise serious questions about the true underlying reasons for its decision.

BP had already acquired 2D and 3D seismic data for the block and completed an environmental impact assessment at substantial cost. It had modelled two prospects in its block located very near the SNE-1 Sangomar field. The Eland prospect had a resource estimate of 936 million barrels of oil (MBO) in-place and 344 MBO recoverable with a total risk of 24%. The Oribi prospect had a resource estimate of 1,180 MBO in-place and 350 MBO recoverable with a total risk of 10%. All that remained was to drill a well, yet BP chose to pay the Gambian government a settlement of $30 million to walk away.

It would be interesting to know the composition of the negotiation team, including the legal personnel on both sides, for this settlement. It remains unclear what factors determined the $30 million settlement and how it was utilised by the Gambian government, as no public disclosure has been made.

BP is a giant in oil and gas exploration around the world, possessing the requisite expertise in exploration and production. It also has a strong due diligence unit that is highly sensitive to corrupt practices in the industry. This sensitivity reflects the UK government’s recently amended legislation on Bribery and Corruption, which covers the activities of UK-listed companies wherever they occur in the world.

BP’s decision to abandon The Gambia came in the aftermath of FAR Ltd.’s failed drilling of the SAMO-1 well, which is adjacent to and on the same trend as BP’s former A1 block. When FAR Ltd drilled SAMO-1, it reported finding no oil accumulation zone but did find traces of oil that may have migrated. FAR Ltd further indicated that the oil migration path from the SAMO well charts towards the Bambo and Soloo wells, which were mapped to be in the same two primary reservoirs as the eight others, and now twenty-three, wells that FAR Ltd and its joint venture partner Woodside Energy have drilled in the SNE-1 Sangomar field. The Bambo and Soloo prospects are even closer to BP’s previously held A1 block than the SAMO-1 prospect.

If BP had any concerns, it did not share them publicly. However, there is no doubt that its decision must have been based on extraordinarily strong reasons that were not in its interest as an investor.

FAR Ltd Laughing all the way to the bank

– Far sold stake in SNE-1 Sangomar

– Full detail of deals.

– Petronas sold back shares to FAR and left JV.

– FAR license exemption in The Gambia

It appears FAR Ltd. has emerged as the winner in the murky affairs surrounding The Gambia’s missing oil and gas. In June 2020, FAR Ltd. was in a dire financial state, having defaulted on its development cash call for the SNE-1 Sangomar field, putting its entire 13% stake in the joint venture at risk. The default clause read:

“Under the JOA default provisions, if a defaulting party has not fulfilled its financial obligations within six months from the date of notification of the default, it will forfeit its participating interest without compensation. Unpaid amounts accrue interest at the LIBOR rate + 2%.”

FAR Ltd. embarked on cost-cutting measures, including making several staff redundant and requiring all senior executives and non-executive directors to accept a 20% salary or fee reduction effective 1 July 2020.

In this abysmal financial context, FAR Ltd. embarked on its now-failed Bambo-1 well and side-track well, which it claimed were not extensions of the SNE-1 Sangomar field. Throughout the pre-drilling preparation, FAR Ltd. was in talks with Woodside Energy, which had issued the default notice and to whom FAR would have had to forfeit its stake if it did not pay up. At that time, Woodside Energy held about 69% of the stake in the SNE-1 Sangomar field.

In July 2021, three months before drilling the Bambo-1 well, FAR Ltd. was forced to sell its entire interest in the Senegal RSSD Project to Woodside Energy to avoid forfeiture without compensation. The transaction was approved at a general meeting of its shareholders on 28 April 2021. FAR Ltd. received a cash payment of US$126 million from Woodside Energy on 7 July 2021. Additionally, FAR Ltd. stands to receive future payments leveraged on the total volume of oil produced from the SNE-1 Sangomar field until 2027.

According to a notice FAR Ltd. issued to its shareholders on 12 June 2024:

“The contingent payment of up to US$55 million is payable in the future based on

various factors relating to the sale of oil from the RSSD Project.

The contingent payment comprises 45% of entitlement barrels (being the share of oil

relating to FAR’s 13.67% RSSD Project exploitation area interest) sold over the previous

calendar year multiplied by the excess (if any) of the crude oil price per barrel (capped

at US$70) and US$58.

The contingent payment terminates on the earliest of 31 December 2027, three years

from the first oil being sold (excluding any periods of zero production), and a total

contingent payment of US$55 million being reached.”

This deal raises very serious and disturbing questions:

- FAR Ltd.’s entire stake in the SNE-1 Sangomar was 15%. This has been revised down to 13% but there is no disclosure of what happens to remaining 2%.

- Was this deal disclosed pre-drilling of the Bambo-1 well to the Gambian public and the government of The Gambia?

- Given FAR’s stakes in the SNE-1 Sangomar field and in The Gambia’s A2 and A5 blocks through its subsidiary FAR (Gambia) Ltd., and its role as the operator during drilling in the Gambian prospects, what measures, if any, were put in place to protect The Gambia against potential conflicts of interest from FAR Ltd especially in the context of question 4 below on migration of oil? PC Gambia (Petronas) could not properly perform this role as FAR Ltd.’s joint venture partner in The Gambia?

- Even if the primary reservoirs in the SNE-1 Sangomar have not extended into The Gambia, does this transaction meet the transparency expected in international investment agreements in oil and gas if oil migrates or has migrated from The Gambia into the SNE-1 Sangomar field?

- What due diligence did Woodside Energy and Petrosen carry out to validate FAR Ltd.’s finding that the SNE-1 Sangomar did not extend into The Gambia’s A2 block and to rule out any possibility of oil migrating from the underdeveloped reservoirs in the Gambian prospects into the SNE-1 Sangomar field?

In August 2022, FAR Ltd. reacquired 100% ownership of blocks A2 and A5 when PC (Gambia) Ltd., the subsidiary of Petronas that previously held the other 50% stake in the blocks, conveniently returned them to FAR Ltd. It is difficult to see the business case for Petronas’s involvement in The Gambia’s A2 and A5 blocks and the justification it provided to its shareholders for taking such an enormous loss willingly.

In the meantime, FAR Ltd. has renegotiated a two-year extension to its exploration licence with the government of The Gambia, exempting it from the yearly commitment to drill a well and all other consequential taxes, fees, and expenses payable to the government.

FAR Ltd. reported that this would enable the company to consider options for delivering value while minimising its expenditure over the two-year extension period. The company aims to capitalise on the exploration data acquired from the two unsuccessful wells already drilled, without significantly drawing down existing capital.

This negotiation with the government of The Gambia would have been heavily influenced by legal advice from members of the same family or connected individuals acting on behalf of both the government and FAR Ltd. It is difficult to justify exempting FAR Ltd. from its contracted drilling obligations and all taxes and expenses payment to the government of The Gambia for the next two years, especially after having received US$127 million plus potential future millions.

There is no official gazette or publication indicating that parliamentary assent has been granted to exempt FAR Ltd. from its tax liabilities to the government of The Gambia. It would be a surprise if there had been. The government of The Gambian remains cash strapped and unable to meet basic needs for hospitals, schools, police, and infrastructure. With this arrangement, FAR Ltd. is arguably recouping every penny it claimed to have spent in The Gambia through its subsidiary under its so-called corporate social responsibility.

In the meantime, FAR Ltd. has outlined its plan for prospects Panthera, Jatto, and Malo in its A2 block, each of which it claims (as it did with the other unsuccessful prospects) contain multiple potential oil-bearing reservoir targets. However, any exploration on these prospects is conditional on FAR Ltd. finding a suitable joint venture partner to fund the cost. Thus, the extension granted to FAR Ltd. is likely to be longer if it cannot find a joint venture partner with deep pockets and one should add relevant expertise. This situation places The Gambia in a precarious position.

Given that the Gambian wells were found not to contain significant oil and gas reserves, it could be argued that FAR Ltd. strategically avoided the costs and risks associated with further exploration and development. However, this outcome also meant it evaded the possibility of discovering and developing untapped resources, which would have required them to pay royalties to the government of The Gambia. The real issue lies in the decision of the government of The Gambia to sign away 100% working interest in its exploration blocks without thoroughly exhausting all possibilities. This decision leaves The Gambia with nothing to show for its potential resources—a short-sighted move that is difficult to justify.

FAR Ltd. would likely point to the extensive cautionary exemption statement in its presentations, which it would claim absolves it of any liability for inaccuracies in its geophysical data.

Senegal/Gambia Relations

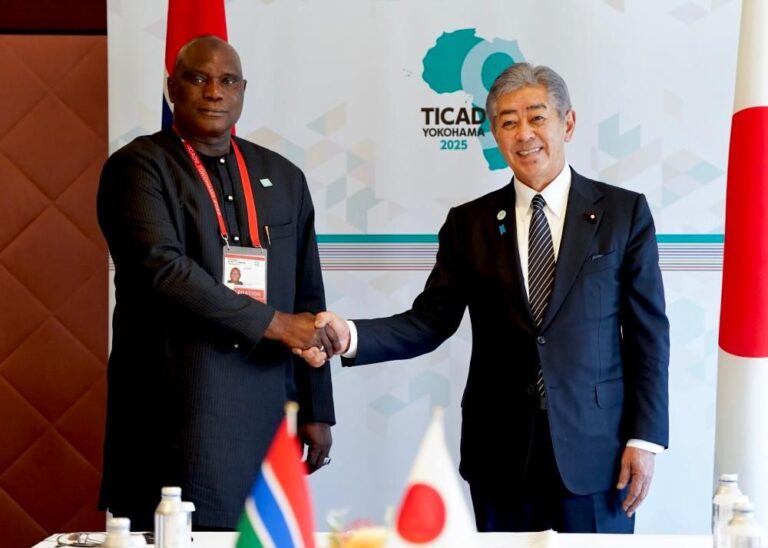

On 24 March 2024, Senegal elected a new president, Mr. Bassirou Diomaye Faye, after Macky Sall was forced by popular pressure to step down at the end of his final term. The new government, with Prime Minister Ousman Sonko at the helm, has vowed to follow and apply principles of honesty in governance. In his inaugural visit to The Gambia, the first since his election, President Faye extended an open arm of cooperation, solidarity, and respect to the government of The Gambia. This reflects his new foreign policy, which places a bold emphasis on unity and solidarity within Africa. He emphasised that the bond between the two countries will be strengthened and that nothing will change from what has already been established. It is hoped that this new government will reflect the level of honesty in governance it has spoken about in its actions, bringing transparency to all matters relating to dialogue, exploration, and production of the shared natural resources between the two countries. However, a recent high-level intergovernmental meeting between the two countries, attended by President Faye, Prime Minister Sonko, and The Gambian Vice President Jallow, focused on key areas of strategic importance but notably omitted the most sensitive topic: oil and gas. This omission raises concerns about future developments.

The curse of oil and gas in African Countries

Oil and gas have been a curse for almost all producing Sub-Saharan African countries. These nations are endowed with vast natural resources that could have propelled them into the league of developed countries. However, they have failed due to sheer mismanagement and chronic corruption. This is what sets them apart from successfully managed countries like Norway, Qatar, and the UAE, which have similar vast resources. Senegal could turn a new and refreshing chapter in resource management in Africa by emulating the successes of Norway—eliminating corruption, strengthening efficient institutions, and setting up a responsibly managed Sovereign Wealth Fund. It will need to act quickly to register any success because the era of oil and gas is rapidly ending as the world transitions to renewable energy. For The Gambia, the curse has struck even before oil and gas are discovered!

Conclusion

The results from FAR Ltd.’s exploration drilling in the SAMO-1, Bambo-1, and Soloo Deep prospects have confirmed the presence of oil. In the cases of SAMO-1 and BAMBO-1, although the reservoirs were of excellent quality, they were unable to trap the oil due to underdeveloped seals. The oil in these prospects likely migrated to an accumulation zone, which remains unidentified. The most likely location of this accumulation zone is in the SNE-1 Sangomar field. However, FAR Ltd.’s inability to identify the accumulation zone or confirm the migration path of the oil leading to speculation about oil migrating to the SNE-1 Sangomar field is due to several factors: its lack of technical expertise and funds, approach to exploration, drilling, and the accuracy of its geophysical survey data.

This failure is not FAR Ltd.’s alone. The government of The Gambia’s policy on oil and gas exploration has also failed at the level of execution. There is a serious lack of transparency in the relationship between Gambians, the government of The Gambia and FAR Ltd. This relationship appears to operate beyond confidentiality and into the realm of secrecy. Given the country’s weak institutions and the lack of proper regulatory oversight on oil and gas exploration, a vacuum is created where important decisions on matters of national interest are made by connected individuals behind closed doors. The national interest is put at risk when the performance of relevant stakeholders cannot be measured or when failures are not sanctioned.

With Senegal progressing at speed with oil production, there is an urgency for the government of The Gambia to expedite its oil and gas exploration with vigour. The exploration should be competently executed to achieve the purpose of finding an accumulation zone in The Gambia or at the very least establish the migration path of the oil from The Gambia to an established accumulation zone across the maritime boundary with Senegal, anywhere within the subbasin. The resources deep under the seabed in the Senegal/Gambia subbasin, in particular the SNE-1 Sangomar field should not be claimed by Senegal alone. It is overly simplistic to rely solely on surface maritime boundaries as the criterion for determining whether a country should share the natural resources below the seabed with its immediate neighbour. Similarly, it should not be necessary to provide evidence of oil and gas migration from The Gambia to the SNE-1 Sangomar field to justify such sharing. The government of The Gambia should initiate proactive inter-governmental dialogue with Senegal for greater clarity and understanding of the hydrocarbon and geophysical formation across their maritime boundaries. They must agree a protocol for joint resource and revenue sharing on exploration and production of oil and gas in the Senegal/Gambia subbasin of the MSGBC.

Successive governments since independence have failed The Gambia on all the indices of development. It is the smallest country in mainland Africa and potentially by far the easiest to develop if it had the right leadership and progressive orientated people. But despite its manageable size and potential natural resources, The Gambia has suffered the misfortune of having extremely poor leadership and an unenterprising population. The wealthy and so-called intellectuals and professionals have become the biggest enablers of the forces both internally and externally that undermine the economic and political sovereignty of the nation. All of these, give weight to previously held reservations that The Gambia cannot be a viable state. The saga of the exploration of oil and gas on The Gambia’s maritime coast and many other recent developments in the nation’s history should open frank discussion by the people about the future of the country. The Gambia is on the cusp of becoming a failed state (if not already) and there is not a flicker of light shining through this long dark tunnel that it has any chance left to its own accord to save itself. Developing a country requires a collective national effort. If this cannot be achieved, an appealing alternative for The Gambia, given Senegal’s new and dynamic leadership committed to justice, might be to consider full integration with Senegal. This would, in a way, correct the injustice of the Berlin Conference, where the two brotherly nations were divided without their consent. But Senegal, wary of its ‘tainted’ oil and gas lottery win, might shut the door on The Gambia. In that case, The Gambia risks drifting into the wilderness and becoming a basket case – an unsettling prospect. The only way to avoid this fate is for The Gambia to build strong institutions and demand its fair share of the resources in the Senegal-Gambia sub-basin. The Gambia must be resolute in this pursuit. For The Gambia, for Justice, for Development!

Reference Material

- Assessment of the Undiscovered Oil and Gas of the Senegal Province, Mauritania,

Senegal, The Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau, Northwest Africa

By Michael E. Brownfield and Ronald R. Charpentier

- The SNE Discovery Offshore Senegal – Moving a Frontier Basin to Emergent

Eric Hathon, Exploration Director, Cairn Energy PLC 12th June 2018

- Lithostratigraphy and Characterisation of Paleocene Limestones for Optimal

Exploitation (Senegal, West Africa): Comparative Study of the Bandia and Popenguine

Quarries by Thiam, Dione, Dieye & Diakher

- THE REPUBLIC OF THE GAMBIA PETROLEUM (EXPLORATION, DEVELOPMENT &

PRODUCTION) BLOCK A5

- FAR Ltd Press Release FAR Ltd Website 12/06/2024