Tanji Fish Landing Site: Fishmongers and Authorities Voice Concerns Over Rising Challenges

Tanji Fish Landing Site: Fishmongers and Authorities Voice Concerns Over Rising Challenges

NYSS Welcomes 15th Batch of 200 Participants to Two-Year National Skills Training Program

NYSS Welcomes 15th Batch of 200 Participants to Two-Year National Skills Training Program

Heavy Rains Wreak Havoc, Leaving Widow with Seven Children Struggling to Feed Her Family

By: Alieu Jallow

Awa Jobe, a widow in Sukuta, is facing extreme hardships as she struggles to feed her seven children. The recent heavy rains have devastated her petty trade business, leaving her without any source of income to support her family.

The widow, who sells locally made food known as “Cherry” in the evening, now finds herself helpless as all her merchandise has been destroyed by the heavy downpour. With no savings or other sources of income, she is unable to provide for her children and other dependents.

“The rains poured heavily, flooding the entire house with water. It spoiled my bag of rice, as well as the bags of cous and maize I had for my petty business. It has had a serious impact on my business, which used to feed my family. I used to borrow and repay while reinvesting the little I had, but now nothing has worked for me,” she decried.

According to Awa, since her husband’s demise three years ago, she has been grappling with the burden of feeding her seven children through her small business. However, the destruction of her petty trade has affected not only her livelihood but also her emotional well-being. As the sole breadwinner, she feels immense pressure to take care of her family. The stress and worry about how to sustain her children, especially during these challenging times, have taken a toll on her.

“It has been very challenging for me to put food on the table, cover school expenses, and provide clothing. It’s only the Almighty Allah who comes to my rescue, as He has decreed it upon me, but the challenges are overwhelming. Although I don’t pay rent thanks to the benevolence of my landlord, without him, I would have faced eviction and found it even harder to secure a place to live.”

On a rainy evening following a long rainy day, we met Awa juggling to meet the demands of her household. Without any regular income, she struggles to provide quality food for her children while also supporting another family that relies on her.

The enduring widow is seeking public support to feed her family and revive her petty business to ensure sustainability without having to beg all the time.

“I am seeking help to feed my children, as that is the only headache I have. Any support toward that end will indeed help, as the little I get is what I use to cook for them to eat, whether it’s delicious or not,” she appeals.

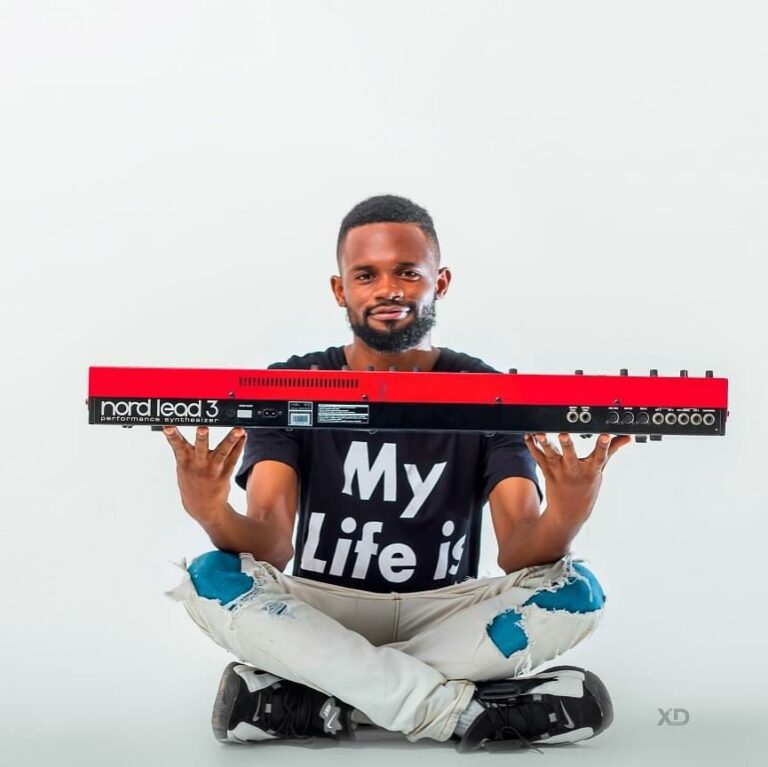

Emmanuel Zahid: A Voice of Hope and Faith in Gospel Music

By Michaella Faith Wright

At 36, Emmanuel Zahid has emerged as a gospel singer whose music transcends mere entertainment, serving as a powerful ministry of faith, hope, and inspiration. From his roots in Sierra Leone to his current base in The Gambia, Zahid has touched countless lives with his soulful voice and unwavering message of hope.

Affectionately known as the “Godfather” in the gospel scene, Zahid’s musical journey has not been without its challenges. Financial constraints and limited access to formal music training marked his early career, but his passion for music and faith never wavered. His rise to prominence is a testament to his determination and belief in the transformative power of gospel music.

Zahid’s performances go beyond the stage, often described as spiritual experiences that deeply move his audiences. His ability to connect emotionally with listeners sets him apart, turning each performance into an opportunity for reflection and worship. One of his most memorable moments came during a performance at the Sonic Shade venue, where his powerful voice resonated throughout the room, silencing the crowd and leaving many in tears.

Born into a family that valued music and faith, Zahid was encouraged from an early age to pursue his passion. By his teenage years, he was already making a name for himself in local church choirs and community events. His path, however, was marked by perseverance and faith, performing in humble settings before gaining recognition.

Beyond his music, Zahid is also a successful marketing executive, balancing his professional responsibilities with his calling to spread hope through gospel. His business acumen has helped him build a strong personal brand, enabling him to promote his music effectively and broaden his reach in a competitive industry.

Zahid’s impact extends far beyond his music. His philanthropic efforts are noteworthy, as he regularly performs at benefit concerts and lends his voice to causes that uplift communities. His commitment to giving back aligns with his belief that his talent is a gift meant to inspire and bring positive change.

As he looks toward the future, Zahid is working on his next album, which he hopes will further solidify his place as a leading figure in gospel music. He also has plans for a series of concerts and tours, aiming to expand his influence and spread his message to new audiences.

Emmanuel Zahid’s journey is one of faith, perseverance, and passion. His music, filled with soulful melodies and heartfelt lyrics, continues to inspire listeners and bring hope to those in need. As he rises in the gospel music world, his legacy of hope and faith will undoubtedly leave a lasting mark.

The Give Back Foundation Network Concludes Summer Skills Training Camp in Marakissa Village

By: Michaella Faith Wright

The Give Back Foundation Network successfully concluded its Summer Skills Training Camp in Marakissa Village, focusing on youth empowerment through leadership, education, and practical skills.

Key speakers, including leadership advocate Ansumana Camara and representatives from the University of Science, Engineering and Technology (USET), urged the youth to embrace responsibility, education, and self-reliance as tools for future success.

Ansumana Camara initiated his closing remarks with an emphasis on the importance of being a good leader, noting: “If you want to move forward in life, you must be a good leader,” he stated, while stressing that leadership is not an easy task. “You need to put yourself together and be a strong leader for your generation.”

During the interactive session, Camara explained the difference between being a leader and understanding leadership, encouraging the youth to embrace qualities such as listening, learning from mistakes, and being calm in difficult situations. He expressed his hope to see a new generation of young leaders who take responsibility, even in small roles, and inspire others. “You can be a leader even in your own home,” he told the youth, “and you should strive to be a leader people are happy to follow.”

Alieu Badara Saine, Registrar at USET, echoed similar sentiments, highlighting the importance of education and leadership among the youth. He spoke about USET’s long history and its commitment to developing applied science programs that equip graduates with practical skills. Saine stressed that youth need to take their education seriously to help transform the country. “We want to see quality youth who take education seriously because it’s the key to progress in this country,” he said, adding that the time to act is now. He encouraged the youth to apply their newly acquired skills, as the world is watching and opportunities are available.

Mariama Colley, USET’s Marketing Sales Officer, reinforced the importance of education for young women. “We want to see every young girl embrace education and empower themselves because education is the key to success,” she stated, encouraging female youth to take advantage of opportunities available to them.

Anus Jatta, Executive Secretary of the Give Back Foundation Network, expressed his pride in the initiative and his commitment to doing more for The Gambia’s youth. He emphasized the need for young people to acquire practical skills that would allow them to be self-reliant and reduce dependence on family support. “We want to see a generation where youth are busy with their own skills and businesses, contributing to themselves and their families,” Jatta said. He also highlighted the foundation’s need for financial support, encouraging partnerships and sponsorships to expand their vision of a self-sufficient and empowered youth population.

Jatta concluded by reaffirming the foundation’s commitment to serving the community and empowering the country’s youth, calling on more support to achieve their goals.

Capacity Building on Mandate of Consumer Commission Extends to Police Officers

Capacity Building on Mandate of Consumer Commission Extends to Police Officers

From 300 Chicks to 1,200: How Ousman Touray is Transforming The Gambia’s Poultry Industry Despite Import Challenges

From 300 Chicks to 1,200: How Ousman Touray is Transforming The Gambia’s Poultry Industry Despite Import Challenges

The Gambia’s Independence Constitution of 1965 and Republican Constitution of 1970

OPINION

By Musa Bassadi Jawara

About a fortnight ago, the Barrow administration announced its intent to gazette a draft constitution that’ll replace the current constitution approved by a national referendum in 1997. This announcement was greeted by a cacophony of protests from politicians, civil society and Gambians from all walks of life. Quite frankly, I was flabbergasted and bamboozled by the sheer lack of religious understanding by participants in the debate of what’s at stake and the macabre path the country is on. In this essay, my goal and objective are to delineate and underscore the vital areas of history embodied in the Independence Constitution of 1965 and the Republican Constitution of 1970.

The Gambia, hitherto now, had been governed by three constitutions: the Independence Constitution of 1965; the Republican Constitution of 1970; and the current 1997 Constitution. On April 24, 1970, The Gambia became a republic following a majority-approved referendum after decades of colonialism. It’s lamentable, tragic and retrogressive in seismic proportion when in 1994, disgruntled and pernicious soldiers of The Gambia National Army marched to the capital, Banjul, seized power, upended constitutional order, overthrew 1970 Republican Constitution and introduced rule by decree. The intervening months and years brought unfathomable hardships on Gambians and autocratic rule of brutal fashion. The carnage was on gigantic scale!

Essentially and frankly speaking, the Republican Constitution of 1970 was not obsolete or stale, it was overthrown by the military. When the military in 1994, subverted the constitution and upended the 30-year-reign of the P.P.P. A cross-section of Gambians rejoiced and celebrated including The Gambia Bar Association (GBA), whose leadership met with the junta and endorsed the coup. It’s ironic that the GBA was supposed to be the bulwark of the Constitution; custodian and the last defense of the Constitution. However, the rest is history. And, time has not been kind to them and yes, the regime that led the country to independence with all its imperfections, the successions since 1994, have plunged the country deeper into poverty, a state of dystopia and destitution.

The time has come to revisit the Republican Constitution of 1970 and use it as a template to formulate a new draft-constitution. Given the bickering, exchange of barbs and demagoguery surrounding the new draft-constitution in the body-politics, there has to be a call to order and reason must prevail in the supreme interest of the nation.

This issue has been politicized and politicians are incapable of setting aside their narrow political interests in favor of what’s best for the country. Gambian politicians and people have a myopic and clouded optics of this constitution issue or debate: this is a sacred document that governs: as a people; as a society; and as a country for future generations yet unborn. To politicize it under intense partisan fighting and gamesmanship will paralyze this country and halt economic and social advancement for decades to come.

Rumors have it that the Republican Constitution of 1997 mimicked the Ghanaian Constitution. Regardless, it was crafted by experts from Ghana and the 2020 draft-constitution was plagiarized from the Kenyan Constitution. Whatever the case, we must go back to the basis and return to old school. This is not about dogma, it’s about common sense and doing the right thing for the motherland, a country that suffered untold barbarity and injustice under dictatorship.

Under the Republican Constitution of 1970, The Gambia had one of the most progressive and vibrant economy in the subregion:

– Cost of bag of rice was under D200; standard and quality of life was not bad.

– Medical services and delivery was one of the best in the sub-region : Bansang Hospital; Kaur Health Center under Chinese medical doctors; and Royal Victoria Hospital were exemplary.

– Gambia Produce Marketing Board (GPMB): had major depots at Kaur, Bansang and Basse with huge rural employment base.

– The Gambia Cooperative Union had microcredit, loan-lending schemes for farmers all across the country.

– The best telecommunication network: GAMTEL rated top three in the whole of Africa.

– The Gambia was crimefree and the murder rate was nil .

– The Gambia’s diplomatic image abroad was stupendous and foreign aid was pouring in and metastasize the length and breadth of the country.

Gambians travel to Europe, America, Asia … name it in large numbers without visa acquisition due to the stellar recognition and image of Gambian passport crafted by the leadership under D.K. Jawara.

– The exchange rate of the Dalasi was in the single digits against major foreign currencies and sadly, on this day, September 3, 2024, the Dalasi exchange rate has crossed over 90 against British Pound Sterling.

To take it down, I’ve concluded that the current breed of politicians have failed the country without exception. There must be and there has to be a new way forward if, this country is to realize its full potential and live out the true meaning of its creed: that we are a country of humankind destined to live in freedom and happiness for all .

All political parties must come to a consensus for the good of the country, thus: let there be a national dialogue to be organized by the state under the chairmanship of the President of the Republic, Mr Adama Barrow.

Thank you.

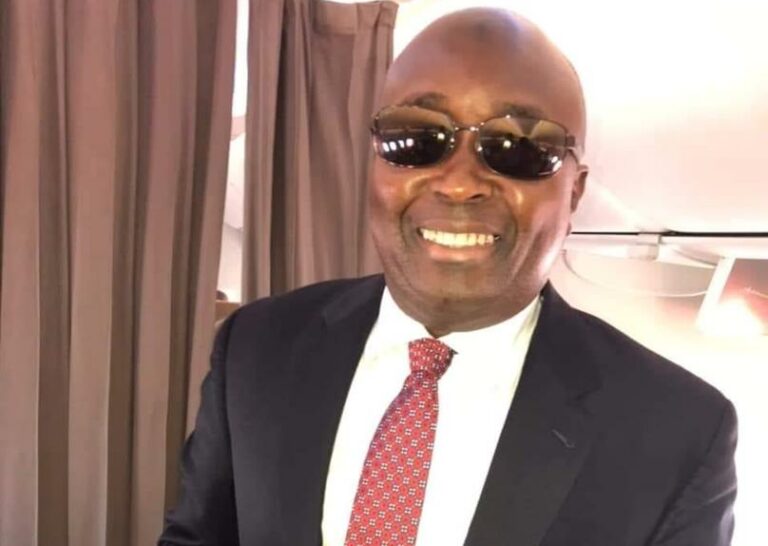

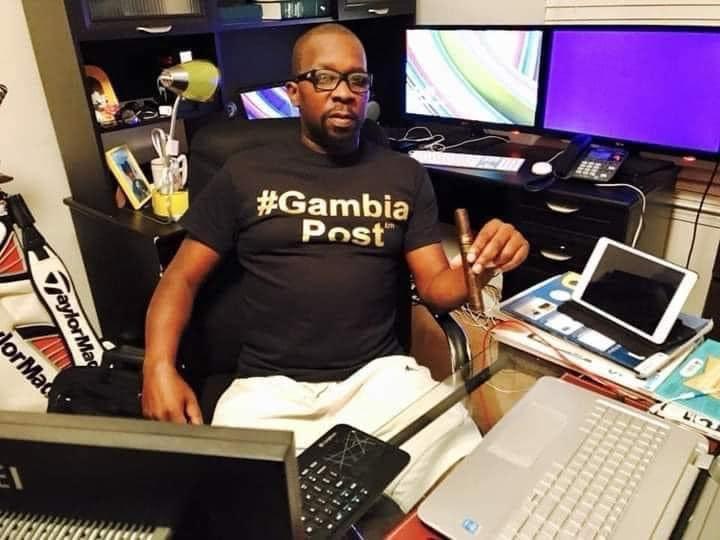

Tribute: George Sarr: A Man. A Plan.

TRIBUTE

By Cherno Baba Jallow

We never met, but from a distance, and from our few email correspondences, George Sarr came off as the consummate gentleman, an amalgam of graciousness and humility.

He died two years ago in the US city of Atlanta.

Sarr’s death is one of those that gnaw at your inner being. This one hits hard. Really hard. But this feeling of dejection over a death has a certain peculiarity to it, for it is over someone you never met, but had a certain affinity for —- for who he was and for what he did for his people and country.

Back in the 1990s, Sarr and colleagues had the foresight to launch The Gambia Post, an online medium to enable Gambians freely express themselves about the tyranny in their country.

The Post’s arrival was highly propitious. The independent press inside The Gambia was barely existing. Freedom of speech was under siege. The people were too scared to speak up against their president (Yahya Jammeh). And newspapers were too scared to publish stories or editorials critical of the president. So:

There was a hunger for information. The Gambia Post provided it in Cyberspace but the information cascaded down from the keyboards to the streets in The Gambia. Many Gambians went to The Gambia Post to read about the happenings in their country. And many of them wrote stuff there. Some of it was outlandish, but most of it was illuminating about the Gambian situation.

I wrote several articles for The Gambia Post, and they were all critical of the former dictator Jammeh. Sarr gave me and several other Gambians an opportunity to write and to inform, to vent out our feelings about the political crisis in our country.

For providing Gambians an outlet to express themselves, and at a time when dictatorship was holding many of them captive, Sarr was rendering an arduous but honorable service to his country. He was a patriot, an unwavering participant in the protracted struggle to bring an end to tyranny in The Gambia.

In 2016, the ramparts of the Jammeh dictatorship finally came crumbling down. Democracy had triumphed. For Sarr and kindred souls, defeating Jammeh and restoring constitutional order was a crowning moment, a moment long in the making. Sarr must have, and deservedly so, patted himself on the back for finally seeing the fruits of his labor. He stayed the course to the very end.

Sarr will remain etched in our memories.

McKinstry Previews Tough Encounters Against Tunisia and Comoros

By: Zackline Colley

The Gambia’s national football team head coach, Jonathan McKinstry, has highlighted the challenges his side faces in their upcoming fixtures against Tunisia and Comoros, emphasizing the different tactical approaches required for each match.

Speaking ahead of the crucial matches, McKinstry described the contrasting styles of the two opponents, noting that each game would demand specific strategies. “They’re two very different games,” McKinstry said. “Comoros are a team that is extremely hard-working. They’re extremely together. They are reasonably direct as a team. They don’t play too much tippy-tappy football. They like to go forward quite quickly.”

McKinstry stressed the importance of neutralizing Comoros’ direct style of play by disrupting their passing game. “If players are unable to play those direct passes, then that threat of runs in behind is somewhat limited,” he noted. “For us, it’s about getting our important players on the ball as often as possible in the best positions on the field. And I think if we do that, we’ll be able to cause Comoros a lot of problems.”

Turning his attention to Tunisia, McKinstry acknowledged the North African side’s experience and potential strategic shift under their new coach. “Tunisia has a very experienced squad, although under a new coach. So obviously, their new coach comes in. These are his first games. And so you will see maybe a strategic change from Tunisia.”

The coach underscored the need for his team to adapt quickly and exploit their strengths, particularly in speed and creativity, while being cautious of Tunisia’s ability to capitalize on space. “We know that Tunisia is a side that doesn’t feel a lot of pressure in games. So we need to make sure that we use our strengths, our speed, our guile, our creativity to cause them problems,” McKinstry explained. “But at the same time, understanding that if we give them too much space, they’ve got players who would punish us in those situations.”

McKinstry also highlighted the importance of squad rotation, given the differing demands of the two matches. He pointed to the inclusion of new players like Lamin Saidy, praising the young goalkeeper’s confidence and skill with the ball. “He’s a very confident goalkeeper. He’s very comfortable with his feet as well. He wants to play; he wants to pass the ball,” McKinstry said of Saidy. “Someone who has a really high save ratio. So someone, I think, at 23 deserves this opportunity to come in and learn from the likes of Ibrahima and Sheikh Sibi, but also to compete for a place on the team.”

As The Gambia prepares for these vital fixtures, McKinstry’s emphasis on tactical flexibility and the integration of new talent will be key to the Scorpions’ success. The matches against Tunisia and Comoros are expected to be intense, with both sides posing unique challenges that the Scorpions will need to navigate carefully.

Justice Minister Debunks Allegations of Lack of Consultation on the 2024 Draft Constitution

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

Justice Minister Debunks Allegations of Lack of Consultation on the 2024 Draft Constitution

National People’s Party (NPP) Strategic Position Ahead of the 2026 Presidential Elections

OPINION

By Bakary J. Janneh

As the political atmosphere in The Gambia evolves, the National People’s Party (NPP), under the leadership of His Excellency President Adama Barrow, is emerging as a formidable contender in the upcoming 2026 presidential pools. The NPP’s strategic initiatives and the current state of opposition parties suggest a potentially favorable outcome for President Barrow and his party at the 2026 pools.

The NPP has demonstrated a remarkable commitment to broadening its support base, particularly in regions such as NBR, LRR and the West Coast Region. This strategic expansion is not just about increasing numbers but also about deeply engaging with communities to understand and address their specific concerns. Party members including influential personalities have been actively involved in outreach programs, town hall meetings, and community development projects, all of which have helped to bolster the party’s image as one that is not only focused on governance but also on grassroots engagement.

This proactive approach has enabled the NPP to penetrate areas previously dominated by opposition parties, thus creating a more balanced political playing field.

In contrast, some opposition parties appear to be struggling with internal conflicts and leadership tussles, which have significantly weakened their ability to present a united front against the National People’s Party. These parties are often seen as embroiled in factional disputes over minor leadership positions, rather than focusing on broader national issues or formulating a compelling alternative vision for the country.

The lack of cohesion within the opposition is a stark contrast to the disciplined and united front presented by the NPP. This disunity not only hampers their ability to campaign effectively but also undermines public confidence in their capacity to govern should they come to power.

While opposition parties are distracted by internal strife, the NPP is diligently preparing for the 2026 elections. The party is working on a comprehensive campaign strategy that aims to consolidate its current gains while also reaching out to undecided voters and those traditionally aligned with the opposition such as the Kiangs and some areas previously dominated by opposition. This forward-thinking approach includes both strengthening party structures and enhancing voter engagement through various platforms, including social media, public forums, and community engagements.

Several personalities like Momodou Sabally, Hon Dou Sanno, Aja Maimuna Baldeh etc are among the generals of NPP spear heading the community engagements via various means such as sport.

The NPP’s preparation is not just limited to political campaigning. There are efforts underway to standardize party operations, improve organizational efficiency, and ensure that all members are aligned with the party’s objectives and vision for the future. This meticulous preparation is likely to give the NPP a significant advantage as the election draws closer.

The party’s proactive efforts to expand its support base, coupled with the disarray within opposition ranks, provide a clear path for President Adama Barrow to potentially secure third term in office.

However, with more than a year to go before the election, there remains room for political maneuvers, alliances, and strategies that could alter the current trajectory. For now, the NPP appears well-positioned to maintain its lead in the race to the State House.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect The Fatu Network’s editorial stance.

Struggle for Food, Water & Shelter: Widow with 7 Desperate for Assistance call: +2203341268

Struggle for Food, Water & Shelter: Widow with 7 Desperate for Assistance call: +2203341268

Amie Sanneh, a middle-aged widow, resides in an isolated area in Abuko near the river with her seven children in a house located on a narrow street.

She sells animal waste to make a living.

Hawa Makasuba, The Gambia’s 25-Year-Old Female Barber Redefining Gender Roles in a Male-Dominated Industry

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

Hawa Makasuba, The Gambia’s 25-Year-Old Female Barber Redefining Gender Roles in a Male-Dominated Industry

Hawa Makasuba, a 25-year-old teacher, makeup artist, and barber from The Gambia, is making waves in a field typically dominated by men.

Despite facing societal challenges and doubts, she has successfully built a thriving barbering business. Hawa balances her multiple roles and uses social media to attract clients, all while providing customer service services.

She shares, “I want to show the world that there’s no fear in pursuing what you love. Barbering brings me income every day, and it helps me take care of my younger siblings.”

Her journey not only inspires other women but also proves that barbering can be a rewarding and sustainable career.

Gambians Strongly Support New Constitution but Doubt Political Parties’ Commitment, Survey Reveals

Gambians Strongly Support New Constitution but Doubt Political Parties’ Commitment, Survey Reveals

Tribute to Lady Justice Mam Yassin Sey- A Fearless Woman of the Law!

By Ba Tambadou

Former Attorney General

It is with sadness that I learned about the passing of Mam Yassin Sey, Lady Justice of the Supreme Court of The Gambia.

After the elections in December 2016 and the political impasse that followed, which exposed and underscored the critical role of The Gambia’s Supreme Court in the nation’s governance system, there was an urgent need to revamp the Supreme Court. The lack of a quorum in the Court and the search for foreign judges to preside over the elections petition case during the political impasse made headlines around the world and became a national embarrassment. We were therefore desperate and determined to show the world that our country, albeit small, had good and decent people capable of serving at all levels of our judicial system including the Supreme Court. We wanted Gambians of high repute, competence and standing to serve in the country’s highest court. We started to search for potential candidates in and outside the country. It was easy for me to identify Justice Mam Yassin Sey as a good judge for our revitalised exclusively Gambian Supreme Court. She had demonstrated on many occasions that she was an independent, competent, fearless, fair and courageous arbiter of the law. She exemplified Lord Denning’s characterisation of a “bold spirit who was ready to allow it if justice so required”. She wasn’t afraid to make difficult decisions no matter the circumstances and even at the risk of losing her job. As one senior lawyer told me, “she was a legal warrior”.

My admiration for justice Mam Yassin Sey was shaped by two encounters with her. The first one occurred back in April 2000 during the students’ demonstration. At the time I was a young lawyer full of passion for justice and human rights and a great deal of reckless energy. When my colleagues and I created the Coalition of Lawyers for Defence of Human Rights under the leadership of lawyer Ousman Sillah, and others like Mariam Denton, Amie Bensouda, Awa Sisay Sabally and Emmanuel D. Joof, we decided to challenge the illegal detention of hundreds of students across the country. We had no instructions from the students or their families. We decided to act pro bono based on our collective conscience and sentiments about the tragic events in the country at the time. A number of students were killed during the protests and a lot more were arrested and detained for weeks. When we filed the case at the high court seeking declarations about the illegal detention of the students and requested for their immediate release, we wondered which judge was going to be assigned the case and, more importantly, if he or she will be brave and courageous enough to make the declarations and to order for the release of the students. It was a very tense period in the country and the stakes couldn’t have been higher. The country was in shock over the killing of unarmed school children in broad daylight and the detention of many more. The government had reacted in such a callous manner because it believed that it was under threat and was therefore determined to crush the threat by any means. The events were unprecedented in The Gambia’s recent history. No one knew what was going to happen next. It was in this tense atmosphere that Justice Mam Yassin Sey was called upon to take a position as the high court judge who was assigned to preside over the case. Before this case, I had appeared before Justice Mam Yassin Sey only once in my very first case as a private lawyer at the high court in a civil matter. I therefore knew little about her and wondered if she was the one. The case was set for hearing and all the lawyers of the Coalition were present in court on that day. There were about ten of us. The courtroom was packed full of families of the students and the press. Our lead counsel lawyer Ousman Sillah made his submissions on our behalf and thereafter the State, which had unsuccessfully attempted to delay the proceedings by requesting an adjournment, strongly opposed our applications for a declaration and release of the students. On the same day soon after the respective submissions by lawyer Ousman Sillah and the State, and unusually for courts in The Gambia at the time, and in the best traditions of the legal profession, Justice Mam Yassin Sey came up to deliver her ruling. It seemed that she had either pre-determined the issues in view of the facts of common knowledge about the killings and mass arrest of students across the country or that it was such a straightforward matter for her that she didn’t need to think long about it since the issues involved the liberty of individuals. Either way, she delivered her ruling with profound dignity, judicial eloquence and the highest standards of competence and professionalism. Without fear, she granted our application and issued a declaration that the arrest and detention of the students violated their fundamental human rights under the 1997 constitution and ordered for their immediate release from custody. We were elated and relieved. Finally, here is a judge who was not afraid to do the right thing even at the risk of losing her job. By this single act of courage and fearlessness, Justice Mam Yassin Sey rekindled my faith in the law. For her though, the issue was simply about justice and legality and nothing else mattered. I wished it were that simple for many of the judges who served our country in those days. The students were subsequently released a few days after her ruling.

My second encounter with Justice Mam Yassin Sey occurred not long after the April 2000 students case, in the matter of the State against Ousman Dumo Saho who was arrested and detained for a prolonged period without trial. He was accused of involvement in a coup plot against the government together with others including Lt Lalo Jaiteh and Lt Dabo. The State’s star witness was a certain Francisco Caso who had come to the country as a businessman in the tourist industry and ended up as the military instructor for the “Junglers”. When Dumo was disappeared and his family and Swedish wife Annika Reinberg could not trace him because all the security services had denied that he was in their custody, I was instructed to act on his behalf. I was joined initially by Emmanuel D. Joof and then subsequently by lawyer Ousainou Darboe during the trial. Upon being instructed, I filed an application before the high court seeking a number of reliefs including that the arrest and continued detention without trial of Dumo Saho violated his fundamental human rights. The case was assigned to Justice Mam Yassin Sey. Based on our prior experience of appearing before her in the April 2000 students case, Mr Emmanuel Joof and I were hopeful that she will do the right thing yet again. True to form, she didn’t disappoint. She rose to the challenge and granted our application. She declared that the arrest and continued detention without trial of Ousman Dumo Saho violated his fundamental rights under the 1997 constitution. Her ruling paved the way for the start of the treason trial that followed and allowed us access to our client at the Mile 2 prisons.

These two cases illustrated her courage and fearlessness. For a better appreciation of the risks Justice Mam Yassin Sey took to serve the ends of justice, we must view her actions in their proper context at the time. Summary dismissal of judicial officers was commonplace sometimes for very flimsy reasons. The political atmosphere was constantly charged, and the government was becoming increasingly intolerant of dissent or alleged threats to their power. There was particular dislike of the courts which were seen as providing the platform for potential check against executive abuse and no effort was being spared to emasculate the judiciary especially in relation to cases that the government deemed “political”. It was in this hostile environment that Justice Mam Yassin Sey delivered her rulings in these two cases and in many others at the time. So even in the darkest days, there were decent Gambian men and women who were guided at all times by conscience and conviction. Justice Mam Yassin Sey was at the top of that list. Unfortunately for our country, her qualities were in demand elsewhere and she subsequently left our shores to serve others.

I remember when I called her in Vanuatu in early 2017 to request her to come back home to serve as a Supreme Court judge. She was excited about it. She didn’t hesitate and never asked about the conditions of service or anything else. She was just happy to have been asked to return home to help rebuild our country. Like many of us who also came back home from abroad following the change of government in December 2016, it was an honour and a privilege to serve our people. Despite the attractions of a better paid job and life abroad, she couldn’t turn it down. It was the mark of a true patriot. The Gambia has indeed lost a good daughter.

May her gentle soul rest in peace.

Can Michelle Obama’s Influence Propel Kamala Harris to Victory in 2024?

OPINION

By Michaella Faith Wright

As the 2024 U.S. presidential race intensifies, Michelle Obama has once again stepped into the political spotlight, delivering a powerful speech that has sparked conversations about the future of American leadership. With Kamala Harris positioning herself as a potential contender against Donald Trump, the question arises: will Michelle Obama’s influence be the deciding factor in helping Harris secure victory in the upcoming election?

Michelle Obama, the former First Lady, captivated the audience with her speech that highlighted the core values of democracy, unity, and the importance of standing up for the future of America. While her words were primarily focused on promoting civic engagement, many political analysts couldn’t help but wonder about the deeper implications of her speech on Kamala Harris’s presidential ambitions.

Michelle’s influence on American politics has remained significant long after she departed from the White House. Her charisma, credibility, and ability to connect with voters have made her one of the most influential figures in the Democratic Party. As Kamala Harris navigates the complexities of the 2024 race, Michelle Obama’s backing could provide a crucial boost.

Harris, who is seen by many as the natural successor to Joe Biden, faces the formidable task of going head-to-head with Donald Trump if he runs. political bases remain strong, and his rhetoric continues to dominate headlines.

However, with Michelle Obama’s track record of galvanizing key demographics, such as ministry voters, women and young people, her support for Harris could ever be a game-changer

Obama’s speech also touched on the importance of empowering women leaders, which further leaders, which further aligns with Kamala Harris’s narrative as the first woman and first woman of colour to serve as U.S. Vice president. Harris has long championed issues such as healthcare reform, climate change, and social justice, areas that also resonate with Michelle Obama’s advocacy.

But will this influence be enough to help Harris over some of the political behemoth that is Donald Trump Political? experts are divided. Some believe that Obama’s endorsement and active campaigning for Harris could swing the election in her base is too loyal and energized to be swayed-the election in her favour, while others argue that Trump’s base is too loyal and energized to be swayed by any endorsement no matter how high profile.

As the race continues to unfold, one thing remains certain. Michelle Obama’s voice will be a powerful force in shaping the narrative of the 2024 election. Whether or not that will be enough to carry Harris Kamala to victory is a question only time to answer.

Music Producer JLive Clears the Air on Dispute with Miz Jobiz

By: Zackline Colley

In a candid interview, renowned music producer JLive addressed rumors surrounding his past working relationship with artist Miz Jobiz. The dispute, which has been a topic of speculation within the music industry, centered on the alleged refusal by JLive to release a song created in collaboration with Miz Jobiz.

JLive explained that the situation stemmed from a misunderstanding about the ownership and financial aspects of the music they created together. According to the producer, while he had provided Miz Jobiz with the songs she initially requested, tensions arose when she sought additional tracks without compensating him fairly.

“The thing is simple,” JLive stated. “I had to give her a song to clarify. I gave her the song she wanted. But she wanted more of the songs—songs which we created together. So I told her straight off that to get those songs, there’s a limited amount that you need to pay. Because at the end of the day, it’s my work, and it’s your work.”

JLive emphasized that his request for payment was reasonable and not excessive, even for an upcoming artist.

Addressing the lack of formal agreements in their collaboration, JLive shared that their partnership was built on mutual trust and potential rather than contractual obligations. “Since I started working with Jobiz as a talent, with the videos and the investment, there was no agreement,” he said. “You see somebody and say this person could be a great person in the future, and you start working with the person. Some people will say it’s very stupid for somebody to do that, but that’s somebody you have love for.”

Despite the fallout, JLive clarified that there are no lingering hard feelings between him and Miz Jobiz. He confirmed that he has since handed over all the songs they worked on together and that their professional relationship has come to an end.

“There is nothing between us at the moment,” JLive concluded. “We might meet somewhere and greet each other, but there is no work relationship between us anymore.”

The revelation sheds light on the complexities of collaborations in the music industry, where creative partnerships can sometimes unravel over financial disagreements and differing expectations. As for JLive and Miz Jobiz, while their professional paths have diverged, the respect they once shared may still linger in their future encounters.

Madiana Besiyaka Nursery School is in dire need of furniture and teaching materials

By: Alieu Jallow

Recognizing the importance of early childhood education and the crucial role it plays in fostering young minds, Madiana Besiyaka Nursery School in Madiana, Kombo South, has called for support as the school grapples with a poor teaching and learning environment.

According to the teacher in charge, Fatou Bojang, the nursery school was initiated to provide early education and care to young children, giving them a foundation for a successful future as the school in the village, with the nearest primary school approximately 4 km away.

The young lady, who is struggling to even receive a proper salary, noted concerns that the school is grappling with a deteriorating roof of raffia palm that leaks whenever it rains. Similarly, she had to improvise furniture by using planks or timber and cement blocks for children to sit on during teaching and learning, which, according to her, is not suitable for young children.

“The school consists of unfinished classrooms with no furniture, very terrible windows, raffia leaves as a roof, an uneven floor with slopes, and the school lacks proper chalkboards that will facilitate proper teaching and learning. The sad reality is that our students are kids and deserve to be taught in a conducive environment,” she decried.

Madam Bojang further outlined that learning activities are mostly disrupted due to the poor condition of the school, especially during the rainy season.

“The problem that we are encountering recently is the lack of furniture, teaching boards, and the floor is not well prepared. With our 75 pupils in one block classroom that is without a roof, when it rains, our classes are disrupted.”

Additionally, she and her colleague decried the lack of proper teaching materials such as books, chalk, and educational resources, thus forcing them to levy D100 per term to buy some of the materials, which has affected their overall education and development. She said that teachers sometimes go without a salary for months, as their salaries are derived from the D100 fees levied on pupils, but the community and parents decried poverty.

“The community and the school agreed to levy D100 per term for a child. From that money, I’m paid, and the balance is used to buy chalks, a drinking bucket, a duster, and a register. But this was only once, after which the payment was never forthcoming, and if you ask parents, they will always tell you that they don’t have money. I have been teaching without a salary simply because of the love I have for these children.”

The nursery school plays a crucial role in the community by providing early education and care to young children, giving them a foundation for a successful future. However, without a good roofing structure, suitable furniture, and teaching materials, the school’s ability to fulfill its mission is severely compromised.

Miss Bojang said the authorities must take immediate action to address the dire needs of the nursery school in Madiana, as providing a safe and conducive learning environment is not only a basic necessity but also a fundamental right for every child. The future of these young children should not be jeopardized; thus, schools should allow the authorities and philanthropists to come to their aid as they resume school after the summer holidays.

“We hope that our plight will be addressed, and your support will do so much for our school and, most of all, for our pupils. This will surely benefit not just the school community but also the community that our school serves to shape the younger generation to make a significant difference for a better future,” she appeals.

Female Barber Hawa Makasuba Challenges Stereotypes in The Gambia

By: Michaella Faith Wright

Hawa Makasuba, a 25-year-old Gambian teacher, makeup artist, and professional barber, is breaking boundaries in the male-dominated world of barbering. Despite societal challenges and skepticism, Hawa has built a thriving business, demonstrating resilience, dedication, and a passion for her craft.

Born and raised in The Gambia, Hawa Makasuba found her passion for barbering a few years ago. While balancing her roles as a teacher and makeup artist, she ventured into barbering to supplement her income and pursue something she genuinely enjoys. Now, at 25, Hawa is committed to this unconventional career path, undeterred by the criticism she faces as a female barber in a male-dominated field.

In an interview with The Fatu Network, Hawa shared some of the hurdles she encounters in her profession. “The first challenge is how people perceive me, and second, the way society passes judgment,” she said. Despite the doubts and rumors, Hawa stays focused on her work. “I do this because I like it, and it helps me pay the bills. Sometimes, you just need to ignore the noise and keep doing what you love.”

Hawa has also encouraged other women interested in the barbering profession, urging them to stay determined. “My message to all the females who want to enter barbering is to stay focused and dedicated. It pays off. Critics are normal in society, but as long as you’re committed, you’ll achieve your goals,” she advised.

With her barbering business thriving, especially during busy seasons like Tobaski and Christmas, Hawa continues to serve clients who seek popular styles like high fades and low cuts. She also emphasizes the importance of customer service in building loyalty, adding that her professionalism and patience have earned her a steady flow of clients. “When customers come to my shop, I make sure they feel welcome and comfortable. That’s one of the reasons I’m not losing customers.”

However, the rainy season presents challenges, as business tends to slow down during this period. To keep attracting new customers, Hawa promotes her work on social media platforms such as TikTok, Facebook, and WhatsApp. Despite her shop being located far from the city, she has managed to maintain a loyal customer base.

As a female barber, Hawa hopes to inspire others by showing that passion and dedication can break societal barriers. “I want to show the world that there’s no fear in pursuing what you love. Barbering brings me income every day, and it helps me take care of my younger siblings,” she said. Her success story proves that barbering is not just a hobby but a sustainable career, especially when one is determined to make it work.

Despite societal criticism, Hawa remains focused on her goals. She continues to thrive as a teacher, makeup artist, and barber, employing assistants to help manage her growing business. “I want to see more women in barbering, not just in The Gambia but across the world,” she concluded.