By Mouhamadou MT Niang

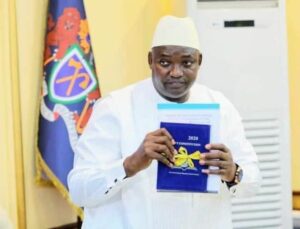

President Adama Barrow is currently on a site visit to assess ongoing construction projects at the Gambia College dormitories and the University of Science, Engineering, and Technology (USET). The visit comes as the government pushes for the completion of these projects ahead of the country’s Independence celebrations next year.

During the visit, President Barrow emphasized the urgency of finishing the work on time, reiterating his administration’s commitment to improving educational infrastructure. To ensure that there are no delays, the Minister of Higher Education, Research, Science, and Technology, Professor Pierre Gomez, announced that the government has made an advance payment of 30 million dalasis to the contractors. According to Professor Gomez, this payment should cover all current expenses.

At the USET sites, President Barrow observed that the actual work differed from what he had been briefed on earlier. The contractors have assured that the work will be completed by November 15, 2024.

Following his visit to the educational sites, President Barrow made his third stop at the state-of-the-art National Emergency Treatment Center construction in Farato. Unlike the previous sites, the President expressed satisfaction with the progress made there, highlighting it as a model for the standard he expects across all government projects.

The President’s visits underscore the importance the government places on timely project completion, particularly in sectors critical to national development

President Barrow Inspects Key Development Projects in Education, Health, and Sports Sector

GPF, Sutura Company Inaugurates Madarasa & Daycare Center; Lands Minister Pledges D20,000

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

GPF, Sutura Company Inaugurates Madarasa & Daycare Center; Lands Minister Pledges D20,000

Resolution Reached: Gambia and Senegal Agree on Border Tracking System

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

Resolution Reached: Gambia and Senegal Agree on Border Tracking System

Brikama Market Vendors Voice Concerns Over Worsening Conditions as Rainy Season Intensifies

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

Brikama Market Vendors Voice Concerns Over Worsening Conditions as Rainy Season Intensifies

Latrikunda Yirignya Water Crisis: Residents Endure 3 to 7 Years Without Clean Water as Authorities Fail

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

Latrikunda Yirignya Water Crisis: Residents Endure 3 to 7 Years Without Clean Water as Authorities Fail

ECOWAS Launches Field Evaluation to Monitor Humanitarian Relief for 2022 Flood Victims in The Gambia

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

ECOWAS Launches Field Evaluation to Monitor Humanitarian Relief for 2022 Flood Victims in The Gambia

Rawdatul Majaalis Press Conference: Group Talks President Election Controversy Amid Emergence of Splinter Group Faction

-

By mouhamadou MT Niang

Rawdatul Majaalis Press Conference: Group Talks President Election Controversy Amid Emergence of Splinter Group Faction

CorpsAfrica/Gambia Hosts Inaugural Pitch Day: Highlighting Transformative Community Projects by First Cohorts

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

CorpsAfrica/Gambia Hosts Inaugural Pitch Day: Highlighting Transformative Community Projects by First Cohorts

Youth Minister Bakary K. Badjie Inaugurates National Youth Conference and Festival (NAYCONF) 2024 with Focus on NDP 2023-2027 and Youth Empowerment

By Mouhamadou MT Niang

Youth Minister Bakary K. Badjie Inaugurates National Youth Conference and Festival

(NAYCONF) 2024 with Focus on NDP 2023-2027 and Youth Empowerment

Kundam Youth Plead for Government Support in Agricultural Tools to Combat Irregular Migration

Kundam Youth Plead for Government Support in Agricultural Tools to Combat Irregular Migration

GCCPC Updates Media on Measures to Enhance Market Competition and Protect Consumers

GCCPC Updates Media on Measures to Enhance Market Competition and Protect Consumers

Inspiring Journey of Female Journalists in The Gambia Achieving Excellence Through Consistency, Hard Work, and Commitment

By Michaella Faith Wright

In The Gambia, a country where journalism plays a pivotal role in shaping public opinion and driving social change, female journalists face unique challenges yet continue to rise and thrive, proving their mettle through consistency, hard work, and unwavering commitment. As a female journalist with a decade of experience in this vibrant media landscape, I have witnessed firsthand the transformative power of dedication in our field.

Consistency is the cornerstone of success in Gambian journalism. It’s about showing up every day, ready to tell the stories that matter in a nation where media plays a crucial role in democracy. For female journalists in The Gambia, this consistency often involves navigating a landscape that is still evolving. Yet, it is this very consistency that builds trust with audiences and establishes credibility. Whether reporting on political developments, social issues, or local events, female journalists are there, day in and day out, committed to bringing the truth to light.

Hard work is the fuel that drives journalistic excellence. In The Gambia, where resources can be limited and demands are high, it means going the extra mile to uncover the details that others might overlook, asking the tough questions, and standing firm in the face of adversity. Female journalists often juggle multiple roles, balancing professional responsibilities with personal commitments. Despite these demands, their dedication to their craft never wavers. They work tirelessly, often behind the scenes, to ensure that every piece of information is accurate, every story is compelling, and every voice is heard.

Commitment is the glue that binds consistency and hard work together. It’s a commitment not just to the profession but to the principles of journalism – integrity, fairness, and the relentless pursuit of truth. For female journalists in The Gambia, this commitment also involves advocating for greater representation and equal opportunities within the industry. It means mentoring the next generation of journalists, sharing knowledge, and breaking down barriers that still exist today.

I am proud to be part of a community of female journalists in The Gambia who exemplify these qualities. Our stories are diverse, but our dedication is a common thread. We are driven by a passion to inform, educate, and inspire. Through our work, we challenge stereotypes, shine a light on important issues, and contribute to the betterment of our society.

In a world where the media landscape in The Gambia is constantly evolving, the role of female journalists remains crucial. Our voices bring balance and depth to the stories that shape public discourse. As we continue to strive for excellence, we pave the way for future generations of journalists, proving that with consistency, hard work, and commitment, anything is possible.

By celebrating the achievements of female journalists in The Gambia and acknowledging the challenges they overcome, we not only honor their contributions but also inspire others to pursue their passions with the same determination. In doing so, we create a media landscape that is richer, more inclusive, and better equipped to serve the public good.