Reed Brody is counsel with Human Rights Watch and a member of the International Commission of Jurists. He is known to Gambians for his work with the victims of ex-president Yahya Jammeh and his role in the campaign to bring to justice in Senegal the former dictator of Chad Hissène Habré. TFN asked Brody about The Gambia’s case against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice which held preliminary hearings on 10-12 December.

Q. What do you make of The Gambia’s decision to bring this case?

A. When we heard that The Gambia was actually going to do this, cheers went up from activists around the world. The slaughter, rape and displacement of hundreds of thousands of Muslim Rohingyas is one of the worst mass atrocities of our time. Before Gambia brought this case, these crimes had largely been beyond the reach of justice.

Q. What can this case achieve?

A. It has already achieved so much. For the first time, streamed live across the globe, and with Myanmar’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi sitting right there, The Gambia’s lawyers laid out, before the highest court in the world, the evidence pointing to Myanmar’s policy of genocide. People in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, where they were chanting “Gambia, Gambia,” finally could feel someone was doing something. While the case may take many years to reach a final ruling, The Gambia asked for provisional measures which could be granted within a month, to stop Myanmar’s genocidal actions. And ICJ orders are legally binding. The long campaign to bring Hissène Habré to justice only reached its goal after Belgium got the ICJ to order Senegal to put him on trial.

Q. But why Gambia?

A. Why not? Should we always leave it to big powers to take these kind of bold international actions? That’s one of the reasons we’re in our current mess. And I think the fact that Gambia is now a democracy trying to come to grips with its own abusive past made it a good champion, as did the Minister of Justice’s personal experiences in Rwanda.

Q. Some people say that with all Gambia’s economic and political problems, why do we need to spend our energies on this?

A. First of all, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation is paying all the fees, so this doesn’t cost The Gambia anything. Indeed, the goodwill and positive publicity that The Gambia is garnering all around the world with this move will certainly comeback to benefit the people of The Gambia, in reputation and recognition.

Q. We’ve heard some victims of the former regime ask why the government is pursuing justice for the Rohingya but not for victims here at home.

A. Obviously, I sympathize with the impatience of many Gambian victims. My main work these days is helping develop a path to bring Yahya Jammeh and his henchmen to justice, and I know that every day without justice is a prolongation of their agony. But the two things aren’t mutually exclusive. We can push on both fronts.

Q. But isn’t it hypocritical by the government?

A. Without getting into value judgments, let me say this. No government has a clean record. When the United States levies sanctions against Jammeh and his family, or speaks out for the rights of the protesters in Hong Kong, we applaud, we don’t say “what about your treatment of Mexicans at the border?” If we can’t get imperfect governments to do the right thing every now and then, the human rights movement would collapse.

Q. Getting back to the ICJ case, what was your impression of the hearings on Gambia’s request for provisional measures?

A. The Gambia presented a compelling case. Gambia had a very tough burden of showing that Myanmar acted with “genocidal intent” but I think its legal team did a great job laying out the evidence. The team is headed by Paul Reichler, one of the most experienced advocates before the ICJ. I’ve known Paul since 1985 when he represented Nicaragua in its landmark victory against the United States for arming counterrevolutionaries seeking to overthrow the government. Back then, he introduced into evidence my report, the first one I ever researched, detailing the atrocities committed by those “contras” against Nicaraguan civilians.

Q. And Myanmar? Why do you think Aung San Suu Kyi represented her country herself?

A. This was clearly for domestic political reasons. With elections coming up there, she wanted to show her support of the military and also to align herself with the majority Buddhist Birmans who hate the Muslim Rohingyas and have mistreated them and denied them basic citizenship rights for over a century. But from an international standpoint, it was a disaster. Usually if someone accuses you of a terrible crime, genocide no less, you try to silence it or avoid talking about it. Here, she rushed to The Hague, guaranteeing the presence and attention of the world’s media. And she didn’t even pronounce the word “Rohingya” which Gambia’s lawyers pointed to as an illustration of how Myanmar denies the group’s very existence. It will also now be impossible for the Myanmar government to say it doesn’t regard the court as legitimate, and to try to ignore any order it may hand down.

Q. What next?

A. Because Gambia requested provisional measures, the court will likely rule in the next month. Then it will take a couple of years to get to the merits of Gambia’s claim.

Q. What’s your prediction?

A. It’s very hard to know. The ICJ is a very, conservative and traditionalist court. It’s mostly made up of former government ministers and it is very loath to step in to the affairs of sovereign countries. And the burden of asking it to do so on an emergency basis, before it has made a full inquiry into the facts, is a very heavy one. But Gambia made the case, I think, and the eyes of the world are on the court.

On three years versus five years: Coalition’s ruination, Gambia’s quandary

Gambians are unequivocally divided on the contentious issue of whether President Barrow should honor the three-year coalition agreement or serve the full five-year constitutional mandate. What is crystal clear though is that the initial euphoria that surrounded the democratic transition is wearing off if it has not worn off already, giving birth to the upcoming politically tense conundrum. The fundamental question to ask is what exactly went wrong, and how did we find ourselves in this sticky situation? An understanding of human behavior is enough for one to be startled but not shocked by our current situation or state of affairs. It is often said that morality is an endangered species, on the verge of being extinct. Since we have abandoned systems of morality for we seem unable or unwilling to live by hopelessly flawed dogma. Some people take the explicit morality route, others take what they can get away with, and there are many who just do what feels right more or less.

In the annals of Gambian politics and our unflinching determination to untether ourselves from dictatorship and tyrannical rule through democratic means, I could not think of anything as monumental as Coalition 2016; a force that ravaged the Babili State House and sent Jammeh packing. With The Gambia being the common denominator that bounds the coalition partners, the fulcrum of that force is the Coalition’s Memorandum of Understanding (aka MOU). Having put an end to a twenty-two-year brutal dictatorship, The Gambia had an opportunity to start afresh. This brought renewed hope that we were heading for posterity. Our biggest shock or disappoint came sooner than later when the formation of cabinet excluded key coalition partners in the PDOIS. The absence of PDOIS in that cabinet was quite startling and many of us found it extremely difficult to come to terms with that unfortunate reality. The leadership of the PDOIS has been asked the fundamental question of whether they were offered ministerial positions or not a dozen times, and from my vantage point I see an attempt to shy away from the question or a deliberate refusal to answer the question for reasons which might be obvious to some but best known to the PDOIS. Every single time that this question resurfaces in an interview, the response from the PDOIS leadership leaves me with more questions than answers, forcing me to ponder whether PDOIS is avoiding to come off in a certain way.

In 2017 Halifa Sallah appeared on Kerr Fatou and was asked this question, and his response was that they were only helping a process and that President Barrow did not see in him that he was interested in a position. The follow-up question to that statement would be because President Barrow did not see in Halifa Sallah that he was interested in a position, so he decided not to offer him a position? On the Perspective Show on GRTS, he was asked the same question once again, and the response from him is that they were never interested in positions. The fundamental question Halifa Sallah is not whether you were interested in a position or not, but whether you were offered a ministerial position? PDOIS were either offered ministerial positions or they were not offered. The situation cannot fall between those two, and the leadership of PDOIS dare not tell us that they do not know whether they were offered positions or not. Personally, I believe PDOIS were offered ministerial positions and they turned down the offers, but they do not want to say this simply because they do not want us to see that they rejected the clarion call to serve the coalition government whose formation they orchestrated from its conceptual stage.

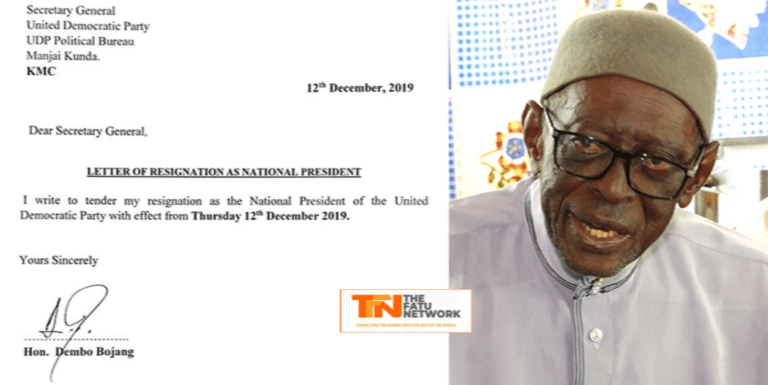

The next wave of disappointment came from the UDP’s Lawyer Ousainou Darboe when he threatened to take to court anybody who attempts to force President Barrow to step down after three years instead of allowing him to serve the full five-year constitutional mandate. I found that statement to be very toxic because it came at a time when national unity was at its embryonic stage and needed to be safeguarded, so anything that could disintegrate it into fragments would undoubtedly be frowned upon. To issue that kind of threat publicly when he could have brought it up in cabinet or in a coalition partners’ meeting for them to find a way to resolve the issue amicably was just uncalled for. Many argued that threat played a major part in the disintegration of the coalition and emboldened President Barrow. Additionally, Lawyer Darboe and Hamat Bah each appeared on the Giss Giss and Kerr Fatou shows respectively in which they both argued that the coalition MOU was never signed. Hamat even challenged the hosts to show him the signed MOU. I struggled to wrap my head around their attempts to find a flaw in the MOU to justify the disregarding or the deliberate flouting of that monumental agreement. If Hamat does not know a lot about contract law, Lawyer Darboe undoubtedly knows that in contract law, there is what is called agreement by conduct. What made Barrow to put his name on the ballot paper at the convention? What made him to resign from the UDP and run as an independent coalition presidential candidate? The conduct of the parties to a contract can constitute an agreement, and President Barrow’s conduct in this case constitutes nothing but an agreement to the MOU. Mr. Darboe challenged or questioned the constitutionality of the three-year agreement. It would be interesting to know if he still maintains that position since that constitution hasn’t been amended yet. In a recent press conference, we saw him present the UDP’s position asking for Barrow to honor the three-year agreement. Many of us find it difficult to identify the clear-cut dichotomy between Lawyer Darboe’s position and the position of the party when he speaks as secretary general and party leader.

We were inundated with another massive wave of disappointment from the coalition partners as a collective when they succumbed to Lawyer Darboe’s threat to take to court anybody who tries to force Barrow to step down after three years. Did that threat leave the coalition partners with no options? Certainly not! The partners knew very well that there was nothing in that agreement that says the President was going to be forced to step down after three years. Instead, he was going to resign on his own accord as per the agreement and this was not going to be an unlawful act nor was it going to be in contradiction to the constitution, hence the resignation provision of the constitution. Could the coalition partners have called for a meeting under the leadership of Madam Fatoumata Jallow Tambajang where they would have reiterated their position on the three-year mandate, making Lawyer Darboe and Barrow understand and possibly accept that the coalition partners were not oblivious of the five-year constitutional mandate? Could the partners have vowed to serve for only three years and then resign should President Barrow choose to extend his mandate beyond the three-year agreement? They knew the constitution has a resignation provision, and the three-year mandate was premised on that provision. Were those options not available to the coalition partners? So how that threat numbed or incapacitated them is beyond comprehension, knowing fully well that the threat was never going to come to fruition because there wasn’t going to be any attempt to force the President to step down. If that threat caused serious damage, what happened to damage control, or why was there no attempt to repair the damage? Was the damage irreparable? The truth be told, most of the partners except for PDOIS were in ministerial positions, and I bet they were not averse to longevity in those positions. To choose to not do something to avert a situation when you had the option to act, and then come back to point fingers at the person who issued the threat as if the country gyrates around that person is just not good enough for people of their caliber. However, this does not absolve the issuer of the threat from responsibility. To add salt to injury, we saw fringe coalition partners convey an emergency meeting, and then advance to the State House to inform the President that they have extended his mandate from three to five years as if the five-year constitutional mandate given to the President is unbeknown to them. Embarrassment and mediocrity characterized that move.

The most gigantic wave of disappointment emanated from the epicenter of this whole conundrum, and that is the President himself. In the early days of his presidency, he said that he wasn’t going to renege on his promise to lead a three-year transition, but that was buried under the carpet soon afterwards. The Gambia slipped and fell into a perilous ravine the very day that President Barrow jettisoned the transition plan and coalition agenda, and welcomed aboard the agenda of self-perpetuating rule. The President got blindfolded by the desire to cling onto power, forgetting what brought him to the State House in the first place. The unfortunate reality is that Mr. President and his inner circle are fixated on cementing their position at the mantle of leadership forcing them to throw over board the very raison d’être of Coalition 2016 thereby jeopardizing the efficacy of the Coalition. The nation is faced with the conundrum of trying to put herself on the right footing amid rampant novice mediocre leadership that is stifling her efforts to head in the right direction. After untethering ourselves from domineering rule, we thought we were going to present to the world our quintessential leader in President Barrow, who was going to lay down that unbreakable solid foundation for subsequent leaders to build on. That has become an illusion. Had the president done what was expected of him per the coalition agreement, or exhibit exemplary leadership by effectively communicating with the coalition partners and the Gambian people on the contentious issue of three or five years, this political quagmire might have been resolved. Instead, the President and the people he barricaded himself with all presumed they have both manpower and firepower to assume absolute control; a reason why they threatened to crush three years ‘jotna’ protesters, at the infamous Brikama rally. Instead of being serene about an imminent peaceful protest, the administration’s protest-phobia and paranoia escalated beyond elastic limits, making it feel like some outcast.

The fundamental question to ask is whether President Barrow should serve three years per the coalition agreement, or the full five-year constitutional mandate under the present circumstance? I dare not ask what is going to happen if the President steps down because the constitution is not ambiguous on that. What is quite obvious though is that the current administration made zero preparation for elections in 2019. Also, I hope I am not under the illusion that if the President were to step down today either voluntarily or forcefully, the vice president would see out the remainder of the term since there won’t be any elections sooner? That is not the spirit of the MOU. Per the coalition agreement, there was going to be a constitutional amendment to enable us go for elections within ninety days of the President’s resignation, and we would have had electoral reforms and other significant changes to prepare the grounds for free and fair elections amid a level playing field. Everything that was supposed to happen for us to go to the polls in 2019 never happened. As a result, I would not say it will be impossible to hold elections now, but the impracticability of doing so is quite obvious. Let us go for five years Gambia for we seem unprepared to hold elections now.

The Operation Three Years Jotna movement’s protest is slated for Monday, December 16th 2019. This movement is going out to express dissatisfaction over the President’s decision to renege on his campaign promise and the coalition agreement. I presume this protest will be peaceful. However, the protesters, the government and its security apparatus ought to be reminded that thuggery and lawlessness will not be condoned because we are a country of laws. We must not sit by and watch familiar places we live in turn into battlefields with some people clearly under the illusion that they can take the law into their own hands without facing the consequences. The protesters should go out to agitate peacefully within the permitted time frame and the parameters of the law, and then disperse to their various homes or wherever they may wish to go. At the same time, the security apparatus is expected to provide the much needed security and not attempt to provoke or be trigger-hungry. Matter of fact, they should employ better crowd control techniques to prevent the situation from escalating. During the political impasse, we showed the world how exemplary we are as Gambians. So let us continue to exhibit remarkable decorum because no progress can be made in a state of chaos and anarchy. Matter of fact, those epitomize failed states today. The Three Years Jotna movement need not attempt to force President Barrow to step down. The President has decided to deliberately flout the MOU by choosing to lead a five-year transition and then have is name on the ballot paper in 2021. The Gambian people will decide whether to retain the current leadership or replace it with a new one come 2021, knowing fully well that being elected to office by the general populace provides no guarantee that national leaders will be effective or dedicated to the national interest . This is a time when we must reason with our heads and not with our hearts. Greed, dishonesty, moral misconduct and other factors should not and must hide our desperate need for guiding principles. Our decisions and actions have more profound consequences than we might think. Finally, I maintain my position that a disregard of the MOU by President Barrow finds him culpable of moral misconduct, compromising his integrity.

The writer, Dibba Chaku, wrote from the United States