By Cherno Baba Jallow

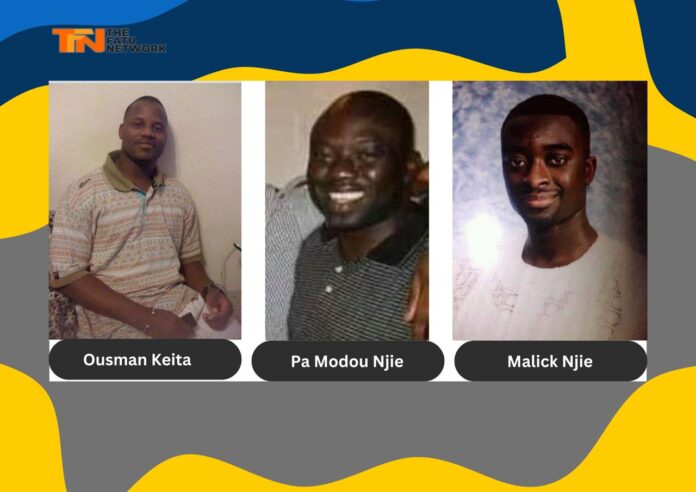

In 2017, Ousman ‘Ous’ Keita died. In the following year, Malick Njie joined him aground. Two years later, Malick’s half-brother Pa Modou Njie also made the final exit from Earth.

Three is a crowd. A crowd of deaths.

Pa Modou, a native of Bansang in The Gambia’s central hinterlands, was my roommate, sharing a two-bedroom apartment together in Detroit. Ous and Malick were my next-door neighbors. Well, sort of. They lived in Southfield, a city on the other side of the 8 Mile Road. The Detroit rapper Eminem sings about 8 Mile —- it’s the dividing line between the city and its suburbs.

Almost every weekend, Pa, Ous and I —- and joined by others, would meet, occasionally in my apartment but usually in Southfield. I would later move to the contiguous city, living in the same apartment complex with Ous and Malick.

Ous, who previously lived in Malmo, Sweden, was the cool dude from Jeswang, Western Gambia. He was tall and well-built —- could have made a good linebacker for any team in professional American football.

He helped throw barbecues every weekend during the summer. He loved to see people get together and eat and tell good, nostalgic stories about events long cleaved from memory.

Ous and I had a falling out — a heated disagreement had left us on non-speaking terms for a couple of years. Our friendship perished. I moved to New York in 2014. But in 2017, I reached out after I got the news that he had been sick. He was receptive. I asked about his health, and we agreed to let go of the past. I kept in contact until he returned to The Gambia and finally succumbed to his illness. The doctor had given him a few months to live.

Malick, born in Banjul, was the consummate gentleman. He was mild-mannered, far from the one to cause an uproar. He had a radiant personality. In gatherings, he talked only when necessary; he was incapable of excessive talkativeness. His English was heavily American-accented. Malick joined his late father in the US during his teens and did his high school here. But he spoke his native Wollof with unimpeachable fluency.

Malick and I were also soccer teammates — he in defence (left full-back) and me in midfield. We played for the Gambian team in Detroit, participating in tournaments across the state of Michigan. We travelled together with the team to Gambian tournaments in many parts of America —- Illinois, Ohio, Georgia and Washington, DC.

Malick’s half bother Pa, who arrived from The Gambia in the mid 2000s, became more than a roommate. He was a big brother who, time after time, counseled me about life. We built a kinship, a kinship forged out of his working relationship with my late uncle Alhaji Yaya W. Jallow. They had been colleagues at The Gambia’s Accountant General’s Office.

Pa attended Armitage High, that school of pre-eminence in the halcyon days of British colonial rule and several years post-Independence.

He was a great and unrelenting cook — the adversities of the kitchen never fazed him. He loved playing scrabble and hated losing. He had deep laughs. He was a big teaser, not in a provocative, but playful, way. He was an agent of joviality.

Pa had been battling diabetes and hypertension. Both Malick and Ous succumbed to colon cancer, the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. The Black Panther movie star Chadwick Boseman and the rapper Too Poetic (Anthony Berkeley) of the now-defunct New York hip-hop group Gravediggaz died of it, too.

The deaths of my former neighbors —-from the same disease and a year apart —- raised an epistemological concern for me: what you don’t know might kill you. I didn’t know anything about colon cancer. But the deaths of my friends forced me to take action. Three years ago, I did a colon cancer screening at the New York City’s Montefiore Hospital. The gastroenterologist, who examined me, said my colon was in perfect condition and that I didn’t need another screen again for the next 15 years.

Perhaps, there is nothing peculiar about the deaths of three friends, and all happening within a span of three years. Life is temporal. People die. Deaths occur all the time. But some deaths are so powerful that they leave some soul-stirring effects in their wake. And they also convey some instructive lessons on the fragility of life.

When death keeps coming back again and again and snatching away people close to you, you are left wondering if you are next in line. Perhaps, this morbid feeling will help launch something of a corrective attitude. Perhaps, it will make you re-examine life and make certain adjustments, if you have to. And before long.