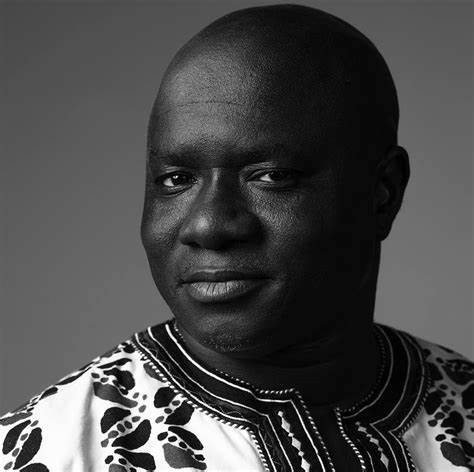

By: Madi Jobarteh

Introduction

The National Assembly which is called Congress, House of Representatives or Parliament in other countries is undoubtedly the most powerful institution in any democracy. This is because the National Assembly carries the greatest responsibilities to ensure that the rule of law prevails, and human rights are protected, and social goods and services are delivered. These responsibilities can be found in multiple places in the 1997 Constitution.

In essence the Constitution places the National Assembly at the heart of accountability in the Gambia. Without accountability there cannot be progress because it is only accountability that tells us if we are making progress or failure or if we are stagnant. Foremost among the institutions bestowed with such responsibility to ensure accountability in our governance systems and development processes is the National Assembly.

This article is therefore aimed at highlighting the role of the National Assembly in the Gambia by pointing out the powers and tools of accountability at its disposal as stipulated in the 1997 Constitution. With those powers and tools, it makes the National Assembly therefore the most crucial and strongest public institution in the country that makes all other institutions perform and abide by the law.

It means the Executive and all institutions within the Gambian society are secondary to the National Assembly contrary to the generally misconceived view that the Executive is the primary state institution. What this means therefore is that it is the National Assembly that can make or break the Gambia. The ultimate goal of this article is to therefore inspire citizens particularly to begin to engage the National Assembly in far stronger and innovative ways in order to support it to play its rightful role in building the Gambia we want.

Some Brief Historical Context

The very history of the parliament itself reflects that power, whether held by an institution or an individual, that is unchecked and unrestrained can become detrimental even onto the very institution or individual that holds it. Probably the first idea of an institution to be known as ‘Parliament’ can be traced to 1215 when landowners or barons in old England rose up against their king to stop him from collecting taxes or imposing levies on them without the prior advice and consent of a royal council.

This rebellion by these barons came to be captured in what is called the Magna Carta that went further to set out several other rights, processes and obligations intended to limit the excesses of the monarchy and to guarantee the rights of these barons, and citizens by extension.

By its history it is clear that the royal council which eventually transformed into the British Parliament, otherwise called the mother of all parliaments, became the key decision maker and check against the monarch hence the Executive in later years until today. Therefore, the parliament in a democracy is the foremost institution that guarantees the protection and the fulfilment of rights and a limitation against the Executive.

But while in the past the parliament was selected from among barons, landowners and the high and mighty of society, modern democratic and republican values provide that indeed the parliament should emerge from the people as representatives entrusted with the power to protect the public good.

From the works of leading western political philosophers such as John Locke, Montesquieu and Tocqueville, who conceived of a new governance system based on separate organs and powers to ensure liberty, justice and prosperity for all, we would see that the functions of a parliament make it the most critical organ in society. It was at this period of world history that the idea of democracy as we know it today began to emerge leading to the emergence of the United States in 1756 as probably the first democratic republic in the world.

Montesquieu’s ideas about separation of powers became the basis of the US constitution, while Tocqueville was a strong advocate of parliamentary democracy which is widespread in western countries under constitutional monarchies. John Locke’s main contribution, in his seminal work ‘The Second Treatise of Government’ debunked the idea of divine rulers claiming that the only legitimate government is one derived from the consent of the people and therefore any government that rules without the people’s consent or violates the contract with the people can be overthrown.

General Overview of the Role of the National Assembly

The National Assembly is the guardian of the people. The National Assembly holds the national purse and determines how public resources such as money are to be spent. The National Assembly is the defender of rights by ensuring that the Executive and all public and private institutions and individuals as well as communities abide by the rule of law. The National Assembly is in charge of national security and individual liberties through checks it places on armed and security institutions of the Gambia.

How the National Assembly performs these tasks can be divided into four main functions.

- Oversight, i.e. by checking and challenging the work of government through robust scrutiny;

- Law-making, i.e. by making or changing laws either proposed by the Executive or by individual members;

- Representation, i.e. by raising and addressing the issues and concerns of its constituents;

- Resource allocation, i.e. by checking and approving taxes and budget to allow government to spend to provide public goods and services.

Section VII of the Constitution is about the National Assembly; its functions, procedures, meetings, dissolution and qualifications of members among others. In addition to its legislative powers as spelt out in Part 3 of this chapter, Section 102 provides for what it calls, ‘Additional Functions of the National Assembly’, as thus:

(a) Receive and review reports on the activities of the Government and such other reports as are required to be made in accordance with this Constitution;

(b) Review and approve proposals for the raising of revenue by the Government;

(c) Examine the accounts and expenditure of the Government and other public bodies funded by public moneys and the reports of the Auditor General thereon;

(d) Include in a Bill a proposal for a referendum on an issue of national concern defined in the Bill, or

(e) Advise the President on any matter which lies within his or her responsibility.

These additional functions clearly give immense powers and tools to the parliament to ensure that public welfare is protected and guaranteed through the delivery of goods and services. These powers enable the National Assembly to ensure that there is efficiency, transparency, accountability and responsiveness of public institutions and officials at all times. Further, they empower the parliament to tackle corruption and abuse of office and strengthen the rule of law and good governance.

In the execution of these functions the Constitution requires under Section 112(b) that NAMs demonstrate integrity and shun corruption and be guided only by their conscience and the national interest. Section 110 even provides protection for the National Assembly and its members such that no one should disrupt or prevent or create any obstacle for a member in the execution of their functions. In fact, from sections 114 to 116 NAMs are protected from prosecution, arrest, detention or forced to serve as witness in a court while traveling to or coming from the National Assembly or merely be in the service of the parliament.

Section 118 protects citizens from criminal liability for publishing reports of the parliament further emphasising not only the power but also the presence of an enabling environment for NAMs to perform their duties. To further expand this enabling environment the Constitution guarantees freedom of expression for NAMs in their debates such that they will not be questioned or impeached (Section 113) for anything they say in parliament!

National Assembly Power over the Executive

The authority that the National Assembly has over the Executive is immense. In the first place the National Assembly serves as an advisory body for the President under Section 102(a) as stated above. Under Section 63 Subsection 3 the National Assembly can pass vote of no confidence in the President thereby sacking the President. Still, the National Assembly can cause the dismissal of the President by impeaching him under Section 67(2) for ‘abuse of office, wilful violation of the oath of allegiance or the President’s oath of office, or wilful violation of any provision of this Consultation’ or if he or she misconducted himself ‘in a manner which brings or is likely to bring the office of President into contempt or disrepute’.

Not only could the National Assembly discipline and dismiss the President, but the parliament can as well dismiss the Vice President and Ministers under Section 75 for poor performance or abuse of office or violation of the Constitution or misconduct. This means where the National Assembly lacks the power under the current Constitution to vet the appointment of the Vice President and Ministers, yet this provision gives the parliament power to restrain, disciple or sack them.

Furthermore Section 77 provides that the President shall report to the parliament at least once a year on the condition of the Gambia and on the policies of the Government and the overall administration of the State. This provision goes further (subsection 3) to oblige the Vice President to answer, in the National Assembly, to matters affecting the President and that the VP and Ministers (subsection 4) are required to answer to requests from the National Assembly anytime to matters under their purview and the general business of the Government.

Hence if there is abuse of power, corruption and inefficiency within the Government then no one is to be blamed other than the National Assembly. This is because the National Assembly has all the powers and tools to control, contain, restrain, reprimand and even sack the entire Executive for poor performance, misconduct of any kind or violation of the Constitution. In fact, by its name, i.e. Executive, it means the Government is merely a law enforcer while such laws are made by the National Assembly which is otherwise called the Legislature, i.e. to legislate. Hence the Executive is answerable to, and only implements what the Legislature has created or approved.

Power over the Judiciary

Not only does the Legislature have powers over the Executive, but it also carries more weight than the Judiciary as spelt out in multiple places in the Constitution. Chapter 8 of the Constitution relates to the Judiciary. While judicial power rests with the courts and the National Assembly cannot interfere with court decisions yet the power of courts could only be exercised as set out by the Constitution and acts of parliament. For example, it is only by an act of parliament can magistrates, Cadi and other lower courts be established under Section 120(1)(b). Section 121 empowers the National Assembly to determine how the Chief Justice is to lay out the procedures and practices of the courts.

Even where the National Assembly does not directly appoint nor vet the appointment of the Chief Justice and other judges (even though a member of the Judicial Service Commission is nominated by the National Assembly) but none of these judges could be removed from office without the expressed participation and consent of the National Assembly under Section 141 subsection 5. Furthermore, the National Assembly determines the salary and other incentives of judges of superior courts (Section 142). Hence the role of the National Assembly in ensuring that the Judiciary obtains job security, receive necessary resources and have the capacity to manage itself point to the fact that National Assembly is instrumental in the functions of the Judiciary.

Power over Other Executive Institutions

Similarly, one will notice that in multiple places of the Constitution, an act of the National Assembly is required in the establishment of public institutions and their procedures, budget, appointments and other functions. These institutions ranging from the civil service, security institutions, public enterprises, or the creation of commissions of any sort. The National Assembly plays oversight function over all state institutions to ensure that they perform efficiently, transparently and responsively according to law.

Through its various select or standing committees, the National Assembly has overwhelming powers and tools to scrutinize every citizen, sector and institution. For example, Section 119 states that a person summoned before the National Assembly or any of its committees to give evidence shall enjoy the same privileges as if one is appearing before a court.

This means in some instances the National Assembly carries the status of a court! Section 109(2) empowers National Assembly committees to even investigate any ministry or a matter of public concern. For that matter subsection 3 gives a committee the same ‘powers, rights and privileges’ of a High Court in forcing any citizen to appear before it as witness and to produce any document and to even examine citizens abroad.

One can go on and on to highlight the powers of the National Assembly, hence to state that the National Assembly is the most powerful and most significant national institution is an understatement. To prove this point, one has to refer to the supreme law to realize that the most mentioned institution in the Constitution is the National Assembly itself. In over 460 places, the Constitution named the National Assembly.

The next most mentioned institution in the Constitution is the ‘President’ at less than 300 times. The name ‘Gambia’ was mentioned only 224 times while the ‘People’ was mentioned only 18 times and ‘Citizens’ 43 times. Superficial as it may sound, to me this indicates that the most important and strategic state institution is the National Assembly.

But just because the National Assembly is the most powerful state institution does not necessarily mean it will therefore always perform its functions according to law in the service and best interest of the nation. For that matter the National Assembly must also be monitored in order to ensure that it continues to effectively perform its functions and not to connive with the Executive under the guise of the law to exploit, oppress and plunder the nation. The words of Montesquieu are therefore pertinent here when he said,

“There is no greater tyranny than that which is perpetrated under the shield of the law and in the name of justice. The tyranny of a prince in an oligarchy is not so dangerous to the public welfare as the apathy of a citizen in a democracy.”

Therefore, I would urge Gambian citizens to not be apathetic and silent on the issues of public welfare and how state institutions, especially the National Assembly handle these affairs. The task before citizens therefore is to be vigilant, active and interested in the affairs of the National Assembly.